Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact | Facebook

The Harmer Who Wore Two Hats (unless he was wearing three)

(John Harmer 1790-1859)

Originally published to Harmer Family Association newsletter 2021

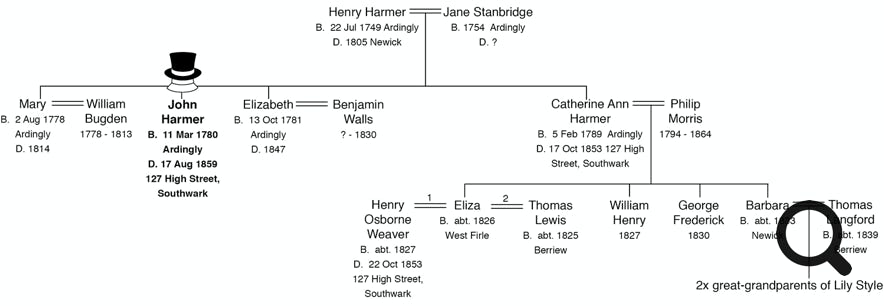

My third great-grandmother Catherine Ann Harmer had an eccentric brother named John who farmed land around the village of Newick, near Lewes in east Sussex. I’m indebted to my great-uncle Frank Langford, an early member of the Harmer Family Association, for gleaning and recording stories of our colourful forebear from his Aunt Jane and Newick residents he met during a circa 1942 visit in which he found “The Harmer Who Wore Two Hats” still well-remembered nearly a century after his death.

The portrait revealed through contemporary research combined with Frank Langford’s gleanings is of a feistily independent and successful Newick farmer who loyally supported his kin. He actively defended his workers, but would punish them too (sometimes creatively). He doggedly challenged the Conservative Party, and commanded honourable treatment despite his ragtag appearance and quirk of wearing two or three hats at any one time.

John Harmer was born on 11th March 1780 in the High Weald village of Ardingly. Of his parents’ four children, he was the only boy. His father, Henry, had relocated nine miles south to Newick by 1798 when Sussex Land Tax Redemption lists him there as an owner occupier. Newick village lies beside the River Ouse in the Low Weald almost exactly half way between Canterbury and Winchester. Thomas Walker Horsfield's 1835 History, Antiquities and Topography of the County of Sussex describes Newick as "a parish containing 1,930 acres of arable, pasture, and wood land [with] sandy loam, very fertile, and capable, by judicious cultivation, of producing crops of almost any kind… pleasantly diversified with hill and dale, and… well adapted for the growth of hops”. Henry Harmer remained in Newick and was buried there in 1805. His only son John, now twenty-five, seems to have adopted the role of father-protector as later records suggest he supported his younger sisters financially, and although he never married, his three sisters were all wed by 1823. Elizabeth was Mrs Benjamin Walls in 1806. His eldest sister, Mary, was Mrs William Bugden living in West Hoathly (close to Ardingly) in 1811, but had died by the time Elizabeth and her young children moved to Lancing near Worthing in 1813. John may have financed her home there. An 1860 auction notice for his estate lists two copyhold coastal residences near South Lancing. One “cottage” had six bedrooms and two sitting rooms; the other three bedrooms and a three-acre market garden. John’s youngest sibling, Catherine Ann, married a farmer named Philip Morris on 20th January 1823. The Morrises were a Catholic family according to Frank Langford’s notes, but their wedding took place in the groom’s Anglican parish church at West Firle (about thirteen miles south-east of Newick). Their marriage record gives Catherine Ann’s residence as Cliffe, on the outskirts of Lewes (about ten miles south of Newick).

John was now (kind of) settled into life as a Newick farmer. He is listed under Newick in an 1832 poll book; won a prize for a plate of currants at Newick Horticultural Society’s fare in September 1833; and is named as a principal Newick landowner in Walker Horsfield's 1835 History of Suffolk. It seems however that this pastoral, prize currant-growing life was not enough for The Harmer Who Wore Two Hats. He was keen to battle the Conservative Party at borough level by maintaining his voting rights for Cliffe. In 1835 The Sussex Advertiser reported that, during voting registration in Lewes, John Harmer had defended his right to remain on the list for Cliffe because he occupied a house there saying, “the furniture there is mine; [and I] reside there when it suits my convenience.” He also had a wily back up argument that property he owned in Newick made him eligible because it was within the boundary of Lewes. The court, however, ruled that “sufficient evidence of residence within the borough had been adduced without going into distance.” His right to remain on the Cliffe voters’ list was upheld, but challenged again the following year. The Advertiser reported on 7th November 1836 that he was objected to by the Conservatives, but had again successfully argued that he rented a house in Cliffe and:

“My sister, nieces and servant live there. The servant is paid with my money. [I] have furniture in the house. The servant generally locks the front door. I have slept there for three or four days in a week between January and July. Live more generally at Newick than elsewhere. Do not know how far it is ; it is less than eight miles off.”

The sister in question was Catherine Ann, now Mrs Philip Morris, and the nieces he talked of were her two daughters. She had borne three children in West Firle, including a girl named Eliza, then returned to Newick in the early 1830s for the birth of her fourth and last child, Barbara. John Harmer surely knew that the true distance between Newick and Cliffe was more like ten miles, and may have exaggerated the number of nights he slept in Cliffe to sway his case, but his account does prove he was paying his sister’s rent (as he appears to have also done for his other sister, Elizabeth in Lancing). It also shows he was determined to vote against Conservative policies.

In addition to challenging Tories, The Harmer Who Wore Two Hats stood up for his workers and their families. He was called as defence witness for the 1840 trial of Philip, the seventeen-year-old brother of Henry Coley, one of John Harmer’s workers. A shopkeeper had accused young Philip Coley of being the thief who’d stolen money from his shop, although he admitted that his only grounds for suspicion lay in the lad’s recent spending spree (which had included rounds of wine, spirits and grog; guns, dogs and ferrets; a silver hunting watch and several articles of new clothing). Henry Coley testified that his brother had stolen the money from a stash under his bed, not from the shopkeeper’s premises. John Harmer (presumably wearing at least two hats) supported Henry Coley’s claim that the stolen money had been his by telling the court that he was a steady, sober employee to whom he’d given a cheque for 10£ the previous April. However, when cross-examined, he confessed that he “could not pronounce Henry Coley to be honest”. Happily for the Coleys, the jury returned a verdict of acquittal.

Not always lenient, John Harmer acted as judge and juror for one of his Newick carters whom he thought lazy. According to Frank Langford’s gleanings (published in Harmer Family Newsletter autumn 1982) he ordered him to drive the cart back and forth and “kept the poor man going to and fro on a bitterly cold day, until he had had more than enough.”

The 1840 tithe map, 1841 census and an 1842 poll book conform John Harmer as resident in Newick as self occupier of copyhold land and owner of Brett’s Farm (whose neat, red brick farmhouse still stands on the village green) with his brother-in-law Philip Morris as its farmer. The 1860 auction notice of his estate describes Brett’s Farm as compact with house, barn, stable lodges and yards and productive arable, pasture, meadow and hop land in a state of high cultivation. He also owned the intriguingly-named Harmer’s Hill (“12 acres of desirable arable, meadow and pasture" near the turnpike on the west entrance to Newick) and three enclosures of “meadow or brook land” at Marbles Meadow in nearby Barcombe Parish. It must by now have been patently obvious that he lived in Newick, and the Conservative Party succeeded in expunging him from the Cliffe voter list in 1842 “on the ground that he was not the boná fide occupier of the house”. Undaunted, he was back in Lewes the following year tendering evidence to support his Cliffe voter rights, but the barrister ruled he had “nothing to do with any name that was not on last year’s list”. The Harmer Who Wore Two Hats may now have at last given up on that particular gambit as there seems to be no further record of him chasing voting rights for Cliffe.

John Harmer’s 1840 testimony that he couldn’t pronounce Henry Coley to be honest resonates when, in 1850, The Sussex Advertiser reports, “Henry Coley, 38, labourer (on bail), was charged with stealing, on 15th December last, 4 bushels of wheat, the property of John Harmer, his master.” According to the Advertiser, Mr Steers, a miller, had spotted one of John Harmer’s sacks in a consignment of wheat sent by Henry Coley. He’d alerted the police and Coley was arrested. True to form, a Coley brother gave evidence and claimed he’d bought the wheat from a Mr Cromp. Under cross-examination, this Coley brother admitted he’d been convicted of horse-stealing twenty-five years before, “but defied anybody to say anything against him since”. However, his testimony was not enough, and thirty-eight-year-old Henry Coley was sentenced to ten month’s hard labour. A quick search through Sussex Advertiser archives reveals the witness to have been Edward Coley, a Newick labourer who was convicted of stealing a bay mare in 1826. It’s not within the scope of this article to explore the wider criminal dealings of the Newick Coley clan, but anyone interested can find them in British Newspaper Archives’ database.

Eliza Morris, John Harmer’s niece, married Henry Osborne Weaver, a Brighton-born draper, in the Methodist Tabernacle, on Lewes High Street on 9th February 1853. The Tabernacle, founded on 6th November 1816, was an imposing, pillar-fronted building, which by the 1850s, held congregations of 500 or more for Sunday morning and evening services. The minister who officiated at their wedding, Rev.d Evan Jones from Monmouthshire, had held office in the Tabernacle since 1826. The wedding was witnessed by Eliza’s brother George Frederick Morris, and a relative of the groom’s mother, Sarah Jane Card. Eliza’s address was High Street, Cliffe, Lewes, and the groom’s High Street Southwark. Henry had been employed as an assistant in the household of a silk mercer on Southwark High Street (sometimes also called Borough) when the 1851 census was taken, and their marital home was a few doors up the road at No. 127. A long “happy ever after” did not transpire for the newly weds. Southwark was then a rough area with many slums. The back streets were described in 1854 as “close, unpaved, ill-drained, vitiated, and vitiating dens.” Cholera claimed the lives of both Eliza’s husband and mother (John Harmer’s sister, Catherine Ann Morris) within five days of each other in October 1851. Eliza remained at the address and married another Southwark silk mercer’s assistant two-years later. Her second husband was a Welshman named Thomas Lewis. The 1861 census shows them occupying the entire house (so not in a slum) with Thomas as a linen draper, and two assistant drapers; a draper’s porter and Thomas’s sister also resident. John Harmer had visited the Lewises in there. According to Frank Langford, when John Harmer arrived at Newick railway station one day planning to travel to London, he was told the train had gone and flew into a temper ordering them to organise a “special” to take him to London instead. When the clerk doubted his ability to afford to charter his own train, he slammed a bag of sovereigns onto the counter, “so he sailed up to London in lordly state, in his own special.” It was during one such visit to the Lewises on 17th August 1859 that he unexpectedly dropped down dead. The Sussex Agricultural Express reported:

SUDDEN DEATH.––An inquest was held on Thursday, at the Half Moon Inn, Borough, before W. Payne Esq., on the body of John Harmer, aged 79, a native of Newick, Sussex, who died suddenly the previous day at Messers. Lewis’s, 127 Borough, were he was visiting. A verdict was returned of “Natural Death.”

His death certificate expands: “most probably diseased heart - natural - died very suddenly”. Frank Langford tells us, “when he died odd packets of money and notes were found all over his home.” Evidently financially eccentric, he died intestate. The Court of Probate at Lewes valued his estate as circa £25,000 (over £2 million in today’s money).

In conclusion, John, the Harmer Who Wore Two Hats, took on his father’s mantel as an immigrant Newick farmer so successfully that the 1860 auction notice of his property included a hill named after him. His life, in addition to growing prize-winning currants, was marked by supporting his workers; younger sisters and their children; pitting his creative wits to maintain voting rights against the Conservatives; and (according to the great-grandson of his sister, Frank Langford) wearing more than one hat at all times. Financially successful, but eccentric, he could afford to charter his own train to London, and left stashes of money all over his home, but it was not in his nature to do anything so mundane as writing a will.