Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact

The Tailor Prince

(First published in the Trafalgar Chronicle in 2021)

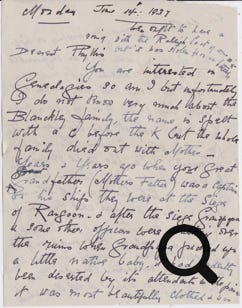

This incredible true story was revealed when I discovered that a family memory concerning my 3rd great-grandfather, Captain Edward Blanckley R.N. dovetailed with a stranger’s family story about her own 3rd great-grandfather, Sophar Rangoon. This dovetailed account begins with an abandoned Burmese princeling found by the British at the start of the first Anglo-Burmese war; meanders through the climbable trees of Kensington Palace gardens; slumps in an impoverished London tailor’s shop; then ends in a comfortable house in leafy Surrey. I first stumbled upon my family’s half of the story when reading a 1937 letter my great-grandaunt Ethel wrote to her niece, which contains this disturbing and intriguing snippet:

Years & years ago when your great-grandfather (Mother’s Father) was a captain on his ship they were at the Siege of Rangoon, & after the siege Grandpapa & some other officers were walking over the ruins when Grandpapa picked up a little native baby. It had evidently been deserted by its attendant in the panic. It was most beautifully clothed & was evidently a young princeling or high born child. Anyway, it was impossible to trace the parents so Grandpapa brought it home with him & when old enough the child was made a page to some lady. It was the fashion then for rich women to have little, dark pages. Afterwards when the child became a man he was set up in London in a tailor’s business & took the name Blanckley after Grandpapa.

Seeking to trace the princeling, I submitted an inquiry to an online genealogical forum, and was very surprised to receive a reply from Annette Hughes, the 3rd great-granddaughter of a high-born Burmese child who had been rescued after the fall of Rangoon and set up in England as a page, then as a London tailor. Our accounts differed, as do words in the game of Chinese whispers, but examination of available facts, in conjunction with her family memories, has left us sure her ancestor, Sophar Rangoon, was the beautifully-clothed princeling described in Ethel’s letter. As Annette’s family had remembered him as known only as ‘Rangoon’, I will refer to him thus in this account of his life.

There are three main discrepancies between Ethel’s account and Rangoon’s story as Annette had understood it. The first discrepancy is his name. In Ethel’s story he took the name Blanckley from Edward. According to Annette’s family tradition, Rangoon was named after the place the British found him, because they hadn’t known his name. The second discrepancy concerns who took him to England. Ethel claims it was Edward Blanckley. Annette believed it was Captain Marryat of Tees (28) who is credited in the only accounts she had found. The third main discrepancy is who the boy was sent to page for. Ethel says it was a rich lady. Annette knows, from plentiful historical documentation, that it was Prince Augustus Frederick, the Duke of Sussex.

There are two accounts of Marryat taking Rangoon to England. Tom Pocock, providing no citation, writes:

The most unusual gift was that of an eight-year-old Burmese boy, whom he had brought home in his ship; said to be a chieftain’s son, Sofar was presented to the King’s brother and sixth son of King George III, the Duke of Sussex, as a page and was soon to be seen at Kensington Palace and Windsor Castle, where he was known as Mr Blackman.

Pocock presumably gleaned his story from an 1872 biography written by Marryat’s daughter, Florence, in which she briefly mentions her father presenting a Burmese page to the duke, saying, “this boy had been brought to England by Captain Marryat”, but made no mention of him having been eight-years-old. Her biography consists, for the main, of copies of her father’s correspondence, as well as the transcript of his captain’s log for the period in which he purportedly took Rangoon onto his ship. There is mention of him carrying a pet baboon and his own son, William, and Pocock further elaborates that he carried several Burmese people including a much-loved three-year-old, nicknamed Billy Bamboo, but neither mentions him transporting a Burmese boy all the way to England and presenting him as a page to the Duke of Sussex.

The Caledonian Mercury contains a different story of a Burmese infant brought on board a British vessel:

At the commencement of the Burmese war, one of the boats of his Majesty's ship Liffey came up with one of the Burmese war boats, when every man on board the latter jumped into the water ; and on boarding the boat, our tars found a Burmese male infant, a few months old. The Serjeant of Marines made prize of the little fellow, and took him on board the Liffey, where he thrives under the care of his nurses, consisting of every sailor in the ship. The Captain intends to bring home the poor foundling, and educate him in England.

This extract of a dispatch from Brigadier-General Archibald Campbell, the commander of the British forces at Rangoon, pinpoints the event to mid-May 1824:

DATE MAY 19, 1824. Information having been received that five rafts were constructing and war boats collecting at no great distance up the river, Commodore GRANT some days ago sent boats of his ship under Lieutenant WILKINSON, of the Liffey, for the purpose of reconnoitring. They fell in with and destroyed one boat (the crew escaping), having seen several others which effected their escape.

Significantly, Annette’s family story is that Rangoon was rescued from a boat or shipwreck by an Englishman and brought to England. However, she had assumed the tiny baby on Liffey was a different child. Pocock, after all, claimed her ancestor had been eight when he was presented to the Duke of Sussex. Further, another of her family stories is that Rangoon recited Burmese lullabies which his daughter sang to her children and grandchildren. She reasoned that a tiny infant would have had no memory of nursery songs. However, it may be worth recalling that, according to Annette, her ancestor was named ‘Rangoon’ because the British crew didn’t know his name. A child of, say, three or four might remember lullabies, but fail to communicate their name. As the Burmese tend to be small in stature, a child of that age could have been presumed younger. Word-of-mouth accounts of the war took several months to travel from Burma to Britain, during which time any ‘Chinese whisper’ effect was bound to increase, so that, for example, a small child in a story might transmute to a tiny baby. Additionally, Annette’s sister recalls their grandmother saying Rangoon had been a baby when he was rescued.

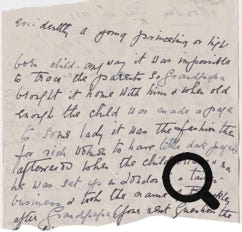

So where was Edward during these events? He was present when the city of Rangoon was taken on 11th May 1824, however, he was neither with Captain Marryat, nor with Captain Coe on Liffey, but a lieutenant on Alligator (28). The Siege of Rangoon Ethel refers to is hard to pinpoint. The arrival of the British fleet in Rangoon harbour had prompted the surprised Burmese to empty the city and flee leaving scorched earth behind them. The only siege, in fact, that took place at Rangoon during Edward’s time there was when thirty-thousand Burmese surrounded the occupying British six-months later. Superior British firepower had prevailed, and the Burmese were driven back on 15th December 1824. The scene Ethel describes of Edward finding an abandoned princeling whilst walking over the ruins would more likely have taken place in mid-May after the civilian population’s flight; and when the infant on Liffey was said to have been found.

Ethel’s claim that the baby was assumed to be a princeling or nobly-born because of his beautiful clothing accords with the strict sumptuary laws governing Burma at this time. Extravagant dress was reserved for nobility. For example, “anklets of gold (kyegyin) were forbidden to all children but those of the royal family on pain of death.” He may possibly have been a son of the fleeing myosa (governor), Mown-Shway-Tha, who was a relative of King Bagyidaw, or of some other member of the Konbaung dynastic family active in the war, such as the King's brother Prince Tharawaddy, who, in 1837, took his children with him in a boat full of troops to overthrow Bagyidaw.

Edward on Alligator arrived in Calcutta on 24th August with the news that King Bagyidaw had decreed the shooting of all bearers of British communication; and that the troops occupying Rangoon were “suffered much by disease”. In fact, 70% of British deaths in the first Burmese War were from tropical illness. Alligator sailed back for Rangoon on 30th December to take command of the British naval force there. Upon rejoining the fleet, Captain Alexander ordered the crews of larger ships to transfer into smaller vessels better able to navigate the Irrawaddy river, with steamship Diana (46) hired to tow them when needed. The flotilla embarked on the five-hundred mile inland journey to the Burmese capital of Ava in January 1825 during the hot, dry season that causes the Irrawaddy to meander “over its sandy bed a slow and sluggish stream”. The princeling, whichever vessel carried him, would have been present as the British fleet and bank-side foot army forced submission from every quarter as it inched implacably closer to Ava, sometimes “under a heavy fire… commanded by the Prince of Sarrawaddy [Tharawaddy]… retreating direct upon the capital, burning and laying waste the villages on his route, destroying all the grain within his reach, and driving thousands of helpless inoffensive people from their houses to the woods.” It was during this progress of conquest, in late April or early May, that Captain Ryves of Sloop Sophie (18) was injured, and Edward was appointed as Sophie’s acting commander. Marryat left Burma in May 1825. Alligator and Arachne (16) remained in Rangoon for the rainy season, but Sophie departed for Calcutta on 16th June in the company of Liffey and Tamar (20) “which she parted with on the 18th, in the gulf of Martaband, in a heavy gale. We can assume the princeling had now left his native country forever, but why was he shipped half-way across the world, instead of being passed to his own people? The Burmese did not, in fact, cede to the British until February 1826. Further, if the princeling was with Edward, he may have been emotionally-drawn to keep him with him. His own newborn son had died in Southampton a month before his departure for the Burma expedition. Departing this soon after his newborn’s burial may have left a baby boy-sized gap in his heart. Later accounts tell of the diligent care he attended a foursome of exotic waterfowl he was attempting to transport home from Chile, but lamented “I lost them one by one during a severe illness on my passage home, in consequence of not being able to attend personally, which I previously did.” It seems probable, therefore, that Edward cared for the princeling in his cabin. Contrarily, on Marryat’ ship, little Billy Bamboo “suddenly sickened and died in the unhealthy confines of the mess-decks."

Thirty-five-year-old Edward’s first voyage as a navy commander was calamitous, if not cringe-worthily embarrassing. Sloop Sophie was caught in a heavy gale off the Nicobar Islands south of the Andamans. The ship was badly damaged (this may even be the boating accident Rangoon remembered) and limped into Calcutta “in a very leaky state,” where the sloop was found unfit for active service. Edward, his crew, and perhaps the princeling, were stranded in Calcutta until, as London Courier and Evening Gazette reported, “The Liffey, Captain Coe, was expected to sail from Trincomalee [Sri Lanka] about the middle of September, and will bring home the late crew of Sofia [sic].” Liffey transpired to arrive sooner, and departed Calcutta on 20th August with “Capt. Blankley, and the officers of his Majesty’s late ship Sophie (sold out of service)”. As you may recall, it was Liffey whom the Caledonian Mercury had named as the carrier a Burmese baby rescued from a boat. It seems probable that it was with Edward Blanckley on Liffey, rather than with Captain Marryat on Tees, that the princeling journeyed to England. The voyage, circumnavigating the Cape of Good Hope, took four months, and Liffey arrived in Portsmouth on 21st January 1826. The Admiralty had formalised Edward’s promotion to commander after Liffey’s final stop at St. Helena, so he disembarked to good news. The portrait of him in Royal Navy commander’s dress coat was likely painted shortly after this return to England with the princeling.

The next detail we know of Rangoon’s life is that he was employed as a page by the Duke of Sussex. As we’ve seen, Marryat’s daughter and Tom Pocock say Captain Marryat presented Rangoon to the duke, with Pocock embellishing that the child was a “gift”, but it’s highly unlikely that the Duke of Sussex, an outspoken abolitionist, would have accepted the gift of a human child. Ethel’s story that the princeling was sent to work as a page when he was old enough, suggests he initially stayed with Edward and his wife Harriet née Matcham (Lord Nelson’s niece). On arriving home from Burma, Edward was quick to rejoin his extended family in Versailles, near Paris, as attested by an April 1827 notice naming him as a recipient of aid donations for a war widow, with the address of 94 Rue Royale, Versailles, a wide, two-storied residence within the grid ordained by Louis XIV, who had commanded the construction of the town in the 1600s. Edward, likely with infant Rangoon in his care, would have attended his father Henry Stanyford Blanckley’s 1828 burial in the cemetery of Versailles. However, by 1831, if not earlier, Edward had taken a south-west England address on Plymouth’s newly-built Union Road close to the Royal Navy dockyard at Devonport. His home there, Raleigh House, was opposite a grand neoclassical bathhouse in a fashionable, modern area. An 1823 guidebook describes the buildings there as “neat and handsome… almost entirely occupied by genteel families, chiefly those of naval and military officers… the new road affords a spacious thoroughfare, and presents to strangers, on their entrance, a succession of neat and uniform buildings.” Edward attended King William IV’s third levee in August 1830, at which the king’s brother, the Duke of Sussex, was also present. Rangoon may have attended in person, or had his potential position discussed. Marryat may even have intervened with the duke, although there is no evidence that he and Edward were close. We cannot know for certain when Rangoon first entered the duke’s household. He is not named as a member of his staff in Royal Kalendars until 1840. From 1826, the Kalendars name only A. Panzara as the Duke of Sussex’s page, then from 1840 until the duke’s death in 1843, the named-pages are J. Dennis and S. Rangoon. However, it seems that only the highest ranked pages were named in the Kalendars, as there are additional pages recorded in other records. For example, reports of the duke’s funeral mention “a mourning coach drawn by four horses, caparisoned with black velvet and feathers, containing Messrs. Barnard and William Beckham, and Rangoon, three of his late Royal Highness’s pages.” Another possibility is that Rangoon was first employed as a page by the duke’s wife Cecilia Underwood. This would accord with Ethel’s family memory of him being sent to work for a rich lady. That the identity of the Duke of Sussex was forgotten need not be surprising. Annette’s line of descendants hadn’t known Rangoon had worked as anything other than a tailor, and when her grandmother mentioned that her sister Dolly believed he’d been friendly with Duke of Cambridge (not Sussex), she’d opined it an unfounded fantasy.

Edward was appointed captain of Pylades (18) in May 1831 for a tour of South America, and took his and Harriet’s only surviving child, eleven-year-old Henry Duncan, with him as a volunteer. Harriet, pregnant again, elected to bear their child in Versailles. This would have been a likely time for Rangoon to take employment as a page in a rich household. It may be that he adopted the first-name Sophar because royal administration required employees to have full names. Sophar is neither a Burmese nor English name. There is an Old Testament name Zophar, and ‘Sophar’ may have been a contrivance of this with 'Sophie’ (the first ship Edward commanded). Although conjecture, this could explain Ethel’s belief that the princeling took Edward’s name when he started work. He doesn’t appear to have used the name ‘Sophar’ with his family. In addition to his descendants remembering him only as ‘Rangoon’; his son Frederick Augustus’s 1880 marriage record, curiously, names the groom’s father ‘William Rangoon’.

Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, rotund and much-loved, was a committed liberal and abolitionist, who “made in his person the royalty popular”, and “whose foot was on the steps of the throne, but whose ‘heart of hearts’ was with the humblest and poorest of the poor [and whose] voice was always raised in the cause of benevolence, and his hand ever outstretched for the relief of the oppressed, whatever might be their creed, their clime, or their complexion.” Rangoon seems to have been granted plentiful freedom within his household. A story passed down through Annette’s extended family is that he climbed every tree in Kensington Palace gardens, and remembered staying in grand houses. Liberal to the bone, neither of the Duke’s two marriages had been sanctioned because he had failed to seek the regal permission required by the Royal Marriages Act. He’d been a loyal friend to Lady Hamilton, having been her and Sir William’s houseguest in Naples, and, later – seemingly non-judgemental of status or pomp – attended her Christmas dinner party when she was confined to debtor’s jail. During this latter event, a fellow guest had been obliged to merrily rip a roast fowl apart with his hands because Emma had no carving knife. One of the surgeons the Duke employed was Thomas J. Pettigrew, who went on to write the Emma-positive ‘Memoirs of the Life of Vice-Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson’ (published in 1849). This amicable Duke was Queen Victoria’s favourite uncle. She was a frequent guest in his home, and he gave her away at her wedding to Prince Albert in 1840.

Rangoon played a prominent, public role in the Duke of Sussex’s lying in and funeral on the 3rd and 4th May 1843. Saint James's Chronicle released the program ahead of the event, telling readers “in a recess at the entrance to the Presence-chamber will stand M’Kay, the piper to the late Duke of Sussex, attired in his rich Highland costume, and in a niche within that room will stand the late Duke’s Rangoon page, attired in Burmese dress…”. It was here that Rangoon’s only known portrait was sketched by an artist for the Illustrated London News. Here is a man so valued, and completely at home in his role within the palace that he has been stationed within the late duke’s presence chamber for the public viewing of this most intimate of royal affairs. Rangoon is not, as Saint James's Chronicle predicted, dressed as an exotic racial curiosity, but attired in British-style uniform with high-waisted pale trousers with a stripe down the side; a tight, lavishly embroidered jacket; cavalry gauntlet gloves; and a magnificent ostrich plume adorning his squared czapka (a light cavalryman’s cap). This garb is likely a version of the court uniform introduced in 1820 by the duke’s brother, George IV, which comprised a dark blue, single-breasted coatee (tail coat), with gold, oak leaf embroidery, and scarlet cloth facings to the high collar and cuffs. Rangoon’s sleeves appear to have been rolled up, although this may have had little significance because there was very little uniformity to early court dress, and his coatee would have been a privately purchased, tailor-made garment. He may have simply preferred to have bare forearms. With one gloved hand lightly touching his breast, Rangoon’s pose is of refined gentility. His expression is mournfully gracious; his head slightly inclined to suggest elegant humility. A half-smile plays on his lips. His eyes gaze to the right, lending him a dreamy look, but the ramrod straightness of his back tells us he is comfortably alert. He looks every inch a prince.

Evocative of the crowd that amassed for Princess Diana’s funeral procession in 1997, on the rainy morning of 4th May 1843 “long before the hour announced for the procession to start, all the avenues leading to Kensington Palace were thronged with spectators”. The solemn procession began to move from the palace a few minutes before eight o’clock, headed by “a detachment of Royal Horse Guards, and a military band playing the Dead March in Saul–– Immediately afterwards followed a Mourning Coach, drawn by four horses, in which were the pages of his Late Royal Highness…”. When the stately procession reached Kensal Green Cemetery, “the Pages of his late Royal Highness were stationed at the entrance of the chapel.” At the conclusion of the funeral ceremony, “his late Royal Highness’s piper, M’Kay, and, indeed all of his late Royal Highness’s servants, seemed deeply affected. They all spoke in the highest terms of his late Royal Highness’s kindness and consideration for them.”

Rangoon married Margaret Sophia Green on 27th February 1844, less that ten-months after the duke’s funeral. Their marriage took place in St. Andrew Holborn, in the City of London. Rangoon, already established as a tailor, gave his father’s name as “a Native of the Kingdom of Ava” with the occupation of “a chief of the Kingdom”. He gave his age as twenty-eight (which may be the source of Pocock’s assertion that he was eight when gifted to the Duke of Sussex), however, declared ages in records such as this are notoriously unreliable, and he may simply have wished to be older than his twenty-two-year-old bride, Margaret. Her father, Thomas William Green, was a fancy cabinet maker who, according to Annette’s research, had made items for Queen Adelaide, and his shop had backed onto a clothier called George Willis & Co., who made items for the royal dukes, including the Duke of Sussex. It could be that this neighbour of Rangoon’s father-in-law had tailored the outfit he’s depicted wearing in the Illustrated London News. It is also possible that George Willis had taught Rangoon the trade (his long-training presumably having taken place before the Duke’s death). At the time of their wedding, both bride and groom were living at 65 Farringdon Street, near Holborn Viaduct in London’s West End. The 1851 census shows this address, and the neighbouring houses, singly occupied by wealthy business-owning families employing servants. The West End at this time was “crowded with bespoke tailors”, with tailoring having been the 4th most common occupation in London when the 1841 census was taken.

Ethel’s knowledge that the princeling was set up as a London tailor suggests that Edward, who was now living in nearby Duke Street, had maintained contact. He died a year after Rangoon’s marriage, on May 4th 1845 following a relapse of tropical illness. Rangoon was left to his own resources. Edward’s son, Henry Duncan was largely away at sea until his early demise in 1854. Edward’s other children were minors at the time of his death. Horace (the child born in Versailles) was about thirteen, and Tori had just turned ten. She evidently knew of Rangoon because our account-giver, Ethel, was her daughter. Tori’s mother Harriet had died of child-bed fever when she was three, and she’d been raised quietly by her reclusive, widowed aunt, Susan Moore née Matcham.

Rangoon and Margaret had six sons and one daughter between 1844 and ’62. As we’ve seen, one child (Annette’s ancestor,) was named Frederick Augustus, presumably after the duke; and another was given the name Edward. Their first son, Sophar, was born in Chelsea, and their second, Shaboo (possibly derived from a Burmese word meaning ‘beloved’) was born in Knightsbridge. However, by 1849, when their third child Thomas was born, they were living in cheaper Lambeth, south of the Thames. Successive birth register, baptism and census records show that Rangoon remained in Lambeth and neighbouring Southwark for the rest of his working life. The family were at No. 22 St Albans Street, Lambeth in ’51, with Rangoon’s given occupation being “tailor journeyman”. According to Working Class Movement Library, journeymen tailors "travelled around the country and stayed at the houses of richer people to make clothes for the whole household. Here, in St Albans Street, the Rangoons had the use of the whole house, as opposed to renting an apartment or room. This detail is significant because Southwark, as for the east-end of London, was a notorious Victorian slum area. The back streets were described in 1854 as “close, unpaved, ill-drained, vitiated, and vitiating dens.” An old woman living in the upstairs of a dilapidated wooden house, where “the ceilings have fallen, the floors are full of holes, and the windows glassless,” said she shared her house with fifteen others, “and we may consider that there are at least the same number in each of the adjoining three tenements.” Bradshaw, writing in 1859, said of Borough, Southwark, “no stranger should trust himself in this locality without efficient protection, the utmost vigilance of the police being found insufficient to repress the acts of robbery still perpetuated occasionally within its precincts”. It should though be borne in mind that not all Southwark-dwellers of this era were vagabonds. Whether in slums or not, many were honest, hard-working families whose struggle to earn enough money to pay rent caused them to frequently shift address.

By 1853, when Rangoon and Margaret’s 4th child was born, they were at 57 Walnut Tree Walk, Lambeth. They were back in Southwark in ’56, at No. 20 King Street, for the birth of their only daughter, named Margaret Sophia after her mother. Her birth certificate declares Rangoon’s profession as journeyman tailor, as it was in the ’51 census. Tailors established in rough areas couldn’t attract rich customers, no matter how good their training or reputation. This could explain why Rangoon had been operating as a journeyman in order to travel to the homes of rich clients. His tailor’s skill, reputation, cultured manners, and former royal patronage would have opened many doors. As a journeyman, he could have earned far more than he could have from a south London address, but at the cost of prolonged periods away from his family whilst resident in clients’ households. Their 6th child, Frederick Augustus, was born in 1859 at No. 1 Marshalsea Place, Southwark. Marshalsea Place was a redevelopment the old Marshalsea Gaol, in which Charles Dickens’s father had once been interred for debt. Dickens, having visited the area in the 1850s, wrote in his preface to the 1857 edition of Little Dorrit, "I came to 'Marshalsea Place: the houses in which I recognised, not only as the great block of the former prison, but as preserving the rooms that arose in my mind's-eye when I became Little Dorrit’s biographer.” When the census was taken two years later, the Rangoons had moved next-door to No. 2, which they shared with five other households. Working long hours for poor pay to scrape the weekly rent together would have been a constant struggle, with poorer London workers commonly prioritising rent over food. By the 1860s, much of the work available to tailors living in low-rent areas comprised up-cycling affordable garments from worn-out clothes. Remaining in Southwark, the Rangoons were at No. 6 St George’s Place the following year; then in Adams Place by ’66, where they remained until at least ’71. A glance at that year’s census shows them sharing the house with four other families, with Rangoon’s occupation given as ‘tailor’ (sans the description of ‘journeyman’).

Pressure on London’s already-struggling working-class increased in the 1870s. A global financial crisis struck in 1873 which triggered an extended economic slump dubbed ‘the great depression’ marking the end of Britain’s industrial golden age. London’s population swelled by 800,000 over the course of this decade, with migrant workers congregating into low-rent areas. By the mid-1870s, the population density of Southwark was almost as great as that of Whitechapel with its infamous slums. Tightened factory regulations had outlawed child labour, but these regulations did not apply to out-sourced work. Factories employed tailors in London’s poorer areas to mass-produce garments from cheap, pre-cut ‘shoddy’ cloth for pittances of pay. These piece-workers were known as ‘sweated tailors’. However, Rangoon’s fate might have been worse had he’d stayed in Burma. In 1852, Tharawaddy’s despotic son, King Pagan, had executed as many as 6,000 of his wealthy and influential Burmese subjects.

Although having lived for many years within this poor area, Rangoon was a survivor, and seems to have maintained pride that his children and grandchildren were princes and princesses of Burma. The family descended from his daughter were told their ancestor was a prince; and Annette's second cousin recounted that she and her siblings used to pretend to be Burmese princes and princesses without having known why.

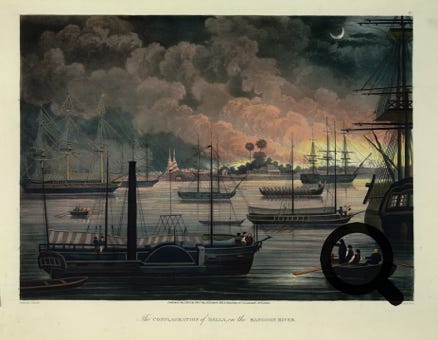

Things had improved for Rangoon by 1881. He and his family were living at No. 4 Rommany Road, with the comparative luxury of sharing their house with only one other family. The census places Rommany Road in Lambeth, and it would be easy to assume that this had been yet another short-distance move. However, further examination reveals the address to have been in a modern brick terrace in rural Gipsy Hill in Norwood, over six-miles south of Southwark. Their out-of-area move can be explained by the presence of Rangoon’s wife’s elderly parents, Thomas and Margaret Green, who’d been living in St. Saviour’s Almshouses, adjacent to Rommany Road, since at least 1871 when the census was taken. St. Saviour’s residents had been relocated from several Southwark almshouses that had been shutdown to make way for railway development. Although the new complex wasn’t completed until 1885, the first wave of Southwark migrants arrived in Gipsy Hill in June 1863, when the opening ceremony of St. Saviour's Almshouses was attended by the Bishop of Winchester and a multitude of named gentlemen with “also a large number of ladies present”. Rangoon’s in-laws had been living in the vicinity of the yard of the White Hart Inn, Southwark High Street when the ’61 census was taken, but may have moved into an almshouse in time to qualify for residency in Gipsy Hill. They appear to have moved there by 1866 when their youngest child, Charles, married in Norwood at St Luke’s.

What, though, caused the Rangoons to wait a decade or more to join the Greens in this slum-free idyll, and what might have enabled them, with Rangoon working as a low-paid Southwark tailor, to afford the higher rent? It may have been that they’d managed to save enough to finance the move; and it may have been that they’d waited for a suitable property to become available (Rommany Road, another new-build, was constructed after the almshouses’ opening). However, an intriguing detail prompts further investigation. In later records, Rangoon’s widow is recorded as the owner of No. 4 Rommany Road, begging the question of how the family had found enough capital to buy a house. One possibility is that Rangoon’s earning power had been high enough in Gipsy Hill to achieve this. Another, while speculative, is intriguing. Edward Blanckley’s sister-in-law, Susan Moore, the wealthy widow who’d raised Edward Blanckley’s daughter, Tori, after her mother died, lived 800 feet (250 meters) from No. 4 Rommany Road. Her home, Gipsy Lodge, was a little house surrounded by fields near the railway station. She and Tori had moved there in the 1850s, and were likely among the unnamed ladies who attended the opening ceremony of St. Saviour’s Almshouses in 1863. Tori moved to a British cantonment in Madras following her 1864 marriage to her cousin William George Ward; and Susan too had moved away. A family with the surname Abrahamson announced the births of children in Gipsy Lodge in 1867 and 1870, and Susan was in Cowley, near Uxbridge, when the 1871 census was taken. She resumed her residence at Gipsy Lodge on or after 1873, when Tori returned from India with six little girls. How likely would it have been for the Greens, having lived in that small community for ten or so years, to have learned that the sister-in-law of the man who’d carried the infant Rangoon from Burma to England owned a house in the village? And how likely also might it have been for them to have made acquaintance with Susan Moore upon her return to the village? Tori too, with her six girls, had moved back into the Gipsy Hill area by 1878 after her husband’s early death. The evidence is circumstantial, but the timing of the Rangoons’ move to Rommany Road; their house’s proximity to Gipsy Lodge; and the mystery over how Mrs. Rangoon had come to own her home, suggest that –just maybe– Edward Blanckley’s wealthy sister-in-law, having learned of the now-adult princeling’s plight, had aided him by setting him up with a decent family home neighbourly close to her own.

When Susan Moore died at Gipsy Lodge in 1885, Tori moved her daughters to Devon, and any sponsorship of the Rangoons ended. Rangoon, at No. 4 Rommany Road, died of pneumonia on 22nd January 1890. His death certificate gives his age as 72, but we can assume him to have been younger. He was buried, poignantly, in an unmarked, common grave in Lambeth cemetery.

In conclusion, despite the discrepancies between Ethel’s account; the limited biographical references for Sophar Rangoon; and the stories remembered by diverse branches of his descendants, we can surmise that the abandoned infant of a Burmese noble was found by an Englishman in May 1824 and taken onto a British ship where he was well-cared for. During his first year on this vessel. We do not know if it was Edward Blanckley who found him, but it seems unlikely to have been Captain Marryat. Ethel’s ‘Chinese whispers’ account is of Edward having found the infant whilst walking through the devastation following the siege, but Rangoon’s memory was of being rescued from a boat or shipwreck, tallying with New Caledonian’s report of a tiny baby, found in an abandoned boat at the start of the war, taken onto Liffey. Records tell us Edward joined Liffey in time for the New Caledonian’s report of the baby on board. Subsequent details of Rangoon working as a page, then as a London tailor match Ethel’s account. It’s feasible that more than one abandoned princeling was carried home from Burma by British officers and took the same career path, but Occam’s razor tells us the simplest explanation is likely correct, and there was just one princeling carried home, and that he was Rangoon (or as Annette puts it, “story gets relayed over the years. Baby, prince, page, tailor. It all fits just the name is wrong.”)

Acknowledgements

Annette Hughes for sharing her extended family’s stories.

Christopher A. Sorensen, Military History & Uniform Consultant - Armed Tender Chatham, Living History Group; and Darrell R. Rivers, Historical Advisor at Historic Insights, for their invaluable knowledge of early 19th century uniforms.

Barbara & Alun Thomas of Norwood Society for their aid in locating the site of Gipsy Lodge.

References

Letter from Ethel Mary Ward to Phyllis Horatia Style dated 14th Jun 18937. Author’s private collection.

Pocock, T., Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer and Adventurer. Stackpole Books (2000) p. 108.

Marryat F., Life and Letters of Captain Marryat, Tauchnitz (1872) p. 96

Ibid. P. 69.

Ibid. P. 91.

Pocock T., Captain Marryat, Lume Books (2000). Kindle Edition. P. 106.

Caledonian Mercury 12 December 1825. Find My Past (accessed January 2021).

Morning Chronicle 12 October 1824. Find My Past (accessed January 2021).

Black J., The British Seaborne Empire. Yale University Press (2004). P. 176.

History of War, the first Anglo-Burmese War, 1823-1826. Online article (viewed January 2021): http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/wars_angloburma1.html.

Wikipedia, Konbaung dynasty, Sumptuary Laws. Online article (viewed January 2021): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konbaung_dynasty#Sumptuary_laws

Scott, J. G., The Burman, His Life and Notions. London: Macmillan (1882). P. 411.

United Service Journal (1829), parts I and II.

Nyiwin's Blog, Nanmadaw Me Nu , Sagaing Min / Bagyitaw, and the First Anglo Burmese War. Online article (viewed January 2021): https://nyiwin.wordpress.com/2013/03/18/nanmadaw-me-nu-%E1%80%94%E1%80%94%E1%80%B9%E1%80%B8%E1%80%99%E1%80%B1%E1%80%90%E1%80%AC%E1%80%B9-%E1%80%99%E1%80%9A%E1%80%B9%E1%82%8F%E1%80%AF-sagaing-min-%E1%80%85%E1%80%85%E1%80%B9%E1%80%80/

John Bull (newspaper) 23rd January 1825.

Robertson, Campbell T, Political incidents of the First Burmese War. Harvard University: Richard Bentley (1853). p.252.

Saint James's Chronicle 12 May 1825. Find My Past (accessed January 2021).

Long W. H., Medals of the British Navy and how They Were Won. Norie & Wilson (1895). P. 290

An account of an embassy to the kingdom of Ava, sent by the Governor-General of India, in the year 1795 by Michael Symes, Esq. Major in his Majesty’s 76th Regiment. London W. Bulmer & Co. 1800. Accessed online (January 2021). Position # 20 https://www.soas.ac.uk/sbbr/editions/file64414.pdf

Burma Library, Narrative of he Burmese War. Online article (accessed January 2021): https://www.burmalibrary.org/en/narrative-of-the-burmese-war-detailing-the-operations-of-major-general-sir-archibald-campbells-army

Long W. H., Medals of the British Navy and how They Were Won. Norie & Wilson (1895). P. 291

Pocock, Tom. Captain Marryat (p. 106). Lume Books. Kindle Edition.

London Courier and Evening Gazette 24 December 1825. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Caledonian Mercury 26 November 1825. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Wikipedia, Treaty of Yandabo. Online article (viewed January 2021): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Yandabo

Ancestry.co.uk, England, Select Deaths and Burials, 1538-1991. Accessed online (2016).

A Naval Biographical Dictionary/Blanckley, Edward. Online article (accessed January 2021): https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Naval_Biographical_Dictionary/Blanckley,_Edward

Blanckley E., Account of the Island and Province of Chiloè. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society (1834). Pp.. 344-361.

London Courier and Evening Gazette 24 December 1825. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Sun (London) 22 November 1825. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

London Courier and Evening Gazette 24 December 1825. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Saint James's Chronicle 24 January 1826. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Pocock, T., Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer and Adventurer. Stackpole Books (2000) p. 108.

Wikipedia, Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex. Online aricle (accessed February 2021): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Augustus_Frederick,_Duke_of_Sussex

Morning Chronicle 24 April 1827. Newspapers.com (accessed February 2021).

1833 Paris p/m letter to Capt Ed Blanckley, Plymouth, England. Webpage (accessed January 2021): https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/1833-paris-m-letter-capt-ed-blanckley-422470670

The Tourist's Companion: being a guide to the Towns of Plymouth, Plymouth Dock, Stonehouse, Morice Town, Stoke and their Vicinities. London, Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown (1823). Pp. 113 and 114

London Courier and Evening Gazette 05 August 1830. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Britain, Royal and Imperial Calendars 1767-1973 Image. Viewed on Find MY Past online (accessed February 2021): https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record/browse?id=gbor%2fkal%2fik_1840%2f0118

Morning Post 05 May 1843. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Kentish Independent 06 May 1843. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Wikipedia, Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex. Online aricle (accessed February 2021): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Augustus_Frederick,_Duke_of_Sussex

Essex Herald 02 May 1843. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Wikipedia, Court uniform and dress in the United Kingdom. Online article (accessed February 2021): https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_uniform_and_dress_in_the_United_Kingdom

Morning Chronicle 05 May 1843. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Kentish Gazette 09 May 1843. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

London Evening Standard 05 May 1843. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

York Herald 06 May 1843. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

British History Online, Farringdon Street, Holborn Viaduct and St. Andrew's church. Online article (accessed February 2021): https://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol2/pp496-513

Gentleman’s Gazette, The History of Bespoke Tailoring: Now and Then. Online article (accessed February 2021): https://www.gentlemansgazette.com/the-history-bespoke-tailoring/

Family Search, England Occupations: Tailoring. Online article (accessed February 2021): https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/England_Occupations,_Millinery,_Quilting,_Patchwork,_Smock_Making,_Staymaking,_Tailoring_(National_Institute)#Tailoring

Working Class Movement Library, Tailors. Online article (accessed February 2021): https://wcml.org.uk/our-collections/working-lives/tailors/

Victorian London - Publications - Social Investigation/Journalism - London Shadows, by George Godwin, 1854 - Chapter 11.

Bradshaw’s Guide Through London, 1859. P. 159

Victorian London, Little Dorrit. Online article (accessed February 2021): https://www.victorianlondon.org/books/dorrit-00.htm

BBC 2, Victorian Slum, TV series. Episode 2. Watched online (February 2021).

Stilwell M., Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll. Social Housing History. Online dissertation (accessed February 2021): http://www.socialhousinghistory.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/London_Housing_Southwark_Philanthropy_Part_1.pdf

Facts and Dtails, the Konbaung Dynasty. Online article (accessed February 2021): http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Myanmar/sub5_5a/entry-3004.html

South London Chronicle 27 June 1863. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

London, England, Electoral Registers, Lambeth, Norwood 1892 – 1908. Ancestry.co.uk (accessed February 2021).

Morning Post 31 July 1867. Find My Past (accessed February 2021).

Daily News 1870. Newspapers.com (accessed February 2021).