Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact | Facebook

A Sussex Shopkeeping Clan

The mercer origins of the Ardingly Harmers

Originally published to Harmer Family Association newsletter 2021

As for many fellow HFA members, my Harmer ancestors hail from Sussex. Mine, however, belong to a mysterious line that bears no known connection to the better-known Heathfield Harmers. This article seeks to unearth the roots of my orphaned-seeming branch of Ardingly Harmers.

Ardingly –whose name is correctly pronounced, Brummie-style, as Ar-ding-LIE– is a village in the High Weald AONB (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) lying approximately thirty-three miles from both London to the north, and Chichester to the south-west. The village has boasted a prestigious private college since 1858. Its alumni, known as "Old Ardinians”, include satirist Ian Hislop.

The first Harmer to appear in Ardingly parish records is a widow, named Elizabeth, who was buried on 21st September 1683. Parish records for Ardingly date back to 1558, so –with no Harmers recorded in them before her burial– the identity of her deceased husband is a mystery. Scrutiny of nearby parish records reveals no likely matches, but it’s a hard fact that not all records from this period have survived. It’s possible that the Harmer family Elizabeth married into were Catholics. Her death took place in the last two years of Charles II’s reformation monarchy. Charles II, unlike his successor and brother James II, was rigidly anti-Catholic, in line with the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell that preceded him. 17th century Catholics were persecuted and obliged to worship in secret, making use of priest-holes to conceal their clergy from protestant investigators. This means they left scant records for the convenience of modern-day genealogists. So it might be that Elizabeth’s marriage took place in Ardingly in a secret, Catholic ceremony.

The next Harmer in Ardingly records is my 6th great-grandfather, John Harmer, who’s identified as a mercer of the village in a 1725 settlement on the marriage of his eldest daughter, Mary, to John Pilbeam, yeoman, of Townehouse Lands, Ardingly. The settlement was witnessed by John Harmer’s eldest son, Thomas. The settlement bears John Harmer’s own signature. He seems to have spelt his surname Harmor, although the clerk writing the settlement refers to him as Harmer.

John Harmer’s 1746 burial record says he was seventy-two, meaning he was born circa 1674. Although we know he married Mary Rootes in Horsted Keynes (three-miles east of Ardingly) in 1698, his date and place of birth are uncertain. There’s a promising-seeming record of a John Harmor, son of John and Susanna, baptised in Heathfield in 1674. As mentioned in the introduction, Heathfield is the ancestral home of many Harmers. However, lying twenty-two miles to the east, it’s not particularly close to Ardingly, and this baptism record seems to be a red herring because additional records trace John Harmor’s life through to his Heathfield burial on 29th December 1743. The only other Sussex-baptised John Harmer, or similar, revealed in records is a child of John and Hester, baptised in Salehurst on 30th March 1673. Although this could be our chap, it’s worth bearing in mind that Salehurst is thirty-miles east of Ardingly. A third John Harmer was baptised in Saint Mary Abchurch, London on 10th February 1675. His father was Francis, and his mother, like the widow buried in Ardingly in 1683, was called Elizabeth.

With available parish records shedding no definitive light, the next recourse is to examine the 1725 marriage settlement, which gives the groom’s residence as “Townehouse Lands”. Shown on more recent maps as Townhouse Farm, John Pilbeam’s residence was at the end of a long lane a kilometre west of the village centre as the crow flies. Townhouse Farm was the subject of a 2017 case study by High Weald AONB Unit. It quotes a 1596 account of “John Pilbeam tenant one messuage and one virgate of land containing by estimation 100 acres called Towneland nup Mascalls.” So the Pilbeams had been established in Townhouse Farm for over a hundred years when Mary Harmer married John Pilbeam in 1725. Parish records reveal that the Pilbeams, unlike the Harmers, were active members of Ardingly’s protestant congregation for the entire course of the 17th century. This suggests the Harmers were fellow protestants, and their absence from parish records prior to 1683 was due to their having resided elsewhere (as opposed to having been locally resident Catholics in hiding).

The 1725 Harmer-Pilbeam marriage settlement provides another clue to the origins of the Ardingly Harmers in its description of John Harmer, the father-of-the-bride, as a mercer of the village. Collins Dictionary defines a mercer as “a dealer in textile fabrics and fine cloth”. A more detailed historical description is given in Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society’s annual journal, Oxoniensia, volume XXXI, published in 1966:

The mercer, though strictly speaking a dealer solely in silks, had during the 16th century and especially in country districts, developed into much more of a general dealer in all sorts of cloth, household articles, and grocery ware… cloths, ribbons, laces, and threads… glassware and stationery, foods and spices… sweets and tobacco, candles and nails, gunpowder and shot, mousetraps and shoehorns, brimstone and treacle, aniseed and arsenic, and all kinds of oddments…”

In other words, village mercers of this era were shopkeepers. The will of Thomas Harmer, proved in 1793, describes him as a shopkeeper of Ardingly and Cuckfield (a village five miles to the south-west). This shopkeeping Thomas was the son of the Thomas Harmer who’d witnessed the 1725 marriage settlement. His mother was Anne née Nicholas.

The surname Nicholas crops up in a 1698 assignment pertaining to a mercer named John Dungate of Shoreham (twenty miles south of Ardingly) which identifies his wife, Hannah, as the daughter of Abraham Nicholas senior of Ardingly. The assignment stipulates “£5 granted to the said Hannah by the said A.N. senr. issuing out of lands called Penlands in Cuckfield”. So property in Cuckfield was bequeathed by the Nicholas family to a daughter married to a mercer. As we’ve seen, Thomas Harmer was a Cuckfield shopkeeper a hundred years later in 1793.

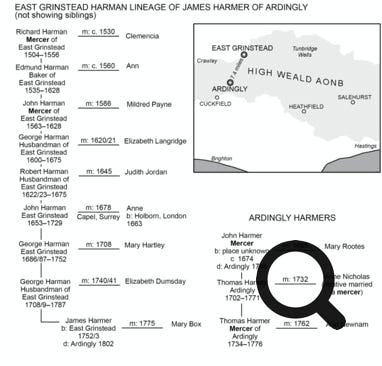

HFA’s December 1992 newsletter (Vol 15. No. 4), by David L. N. Harman, meticulously traces the author’s Sussex roots to his earliest-known ancestor, Richard Harman: a mercer living in East Grinstead during the reign of Henry VIII. Richard Harman’s grandson, John (b. 1563) was also a mercer of that village. East Grinstead lies an easy horse-ride, seven-and-a-half miles, to the north-east of Ardingly. Could the Tudor mercer Harmans of East Grinstead be the forebears of the 18th century Harmers of Ardingly?

David L. N. Harman notes that, over the course of centuries, the surname Harman transmogrifies to Harmer:

“The main spelling variants include HARMAN, ARMAN, HARMON, ARMON, HARMAND, HARMOND, HERMAN, HERMON, JARMAN, many Harman's etc. I have found eventually turn out to be HARMERS.”

East Sussex Record Office hold a 1586 record of an East Grinstead yeoman named John Dungate. This is the surname of the mother of Anne Nicholas who married Thomas Harmer (witness to the 1725 Harmer-Pilbeam marriage settlement) in 1731. The only Harmer I’ve found in East Grinstead parish records before the 1700s is Alexander, son of Alexander and Mary, baptised 1659.

David L. N. Harman traces his East Grinstead Harman ancestors from the 1500s through to the 1749 baptism of James Harman, son of George & Elizabeth. Intriguingly, after this James Harman moved to Ardingly, parish records transcribe his surname as Harmer, not Harman. He is James Harmer in the 1775 record of his marriage to Ardingly local, Mary Box; and James Harmer in his 1802 burial record. Why would a man baptised Harman in East Grinstead have been named Harmer in Ardingly records? It would surely be strange for a “typo” like this to be repeated in parish records 27 years apart. Bearing in mind David L. N. Harman’s observation that Harman mutates to Harmer, the most likely explanation seems that East Grinstead-born James Harman was kin of the Ardingly Harmers so adopted their surname-spelling when he settled in Ardingly.

Evidence maybe be largely circumstantial, but it seems apparent that, 1) the Ardingly Harmers hailed from a mobile clan of 16th and 17th century Sussex mercers, and, 2) they were related to the Harmans of East Grinstead, who were mercers in the time of Henry VIII.