Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact | Facebook

A snapshot of 1841 South Brent

(first published on South Brent Archive’s webpage in May 2023)

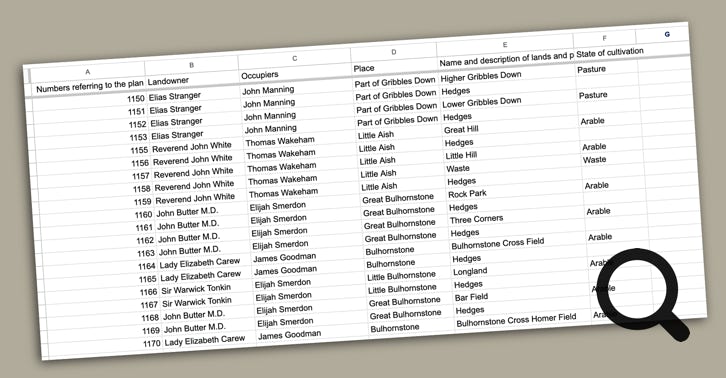

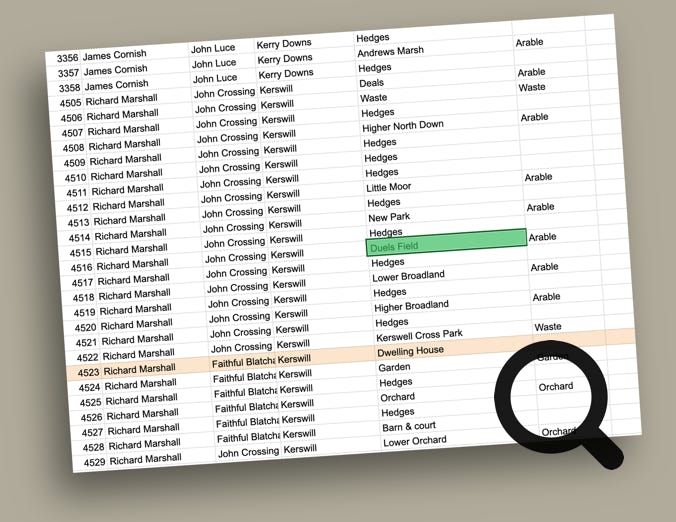

This Archive blog article is developed from notes penned when I transcribed the 5,000 odd entries in South Brent’s tithe apportionment to create a searchable database.

If you’re not familiar with tithe maps, they’re a detailed record of land use and ownership in England and Wales circa 1840, similar to the more famous Domesday Book of 1086, but much more detailed. Every speck of land is numbered for identification in the map’s accompanying tithe apportionment list. The resulting data contains such an astonishing quantity of detail that individual hedges are mapped and named.

On top of this goldmine of historic data, the first census of England and Wales was carried out in 1841: the exact same year in which South Brent’s tithe map was published.

A major quandary has been whether entries in the “Name and description of lands and premises” column are joined or not, because the cursive script flows between words. For example, plot #2173, in Higher Lutton, looks like “great stonepark”, but plot #2184 (“little stone park”), also in Higher Lutton, has clearly spaced words (illustrated: right).

Place names are frequently spelt differently in the tithe apportionment and 1841 census, despite both having been published in the same year. For example, Great Aish in the tithe apportionment is spelt “Great Ash” in the census; Yelland in the tithe is “Yeoland” in the census; and the tithe’s Merrifield is “Merry Field” in the census. So, the spellings aren’t fixed. After all, they were passed down by word of mouth (not quill).

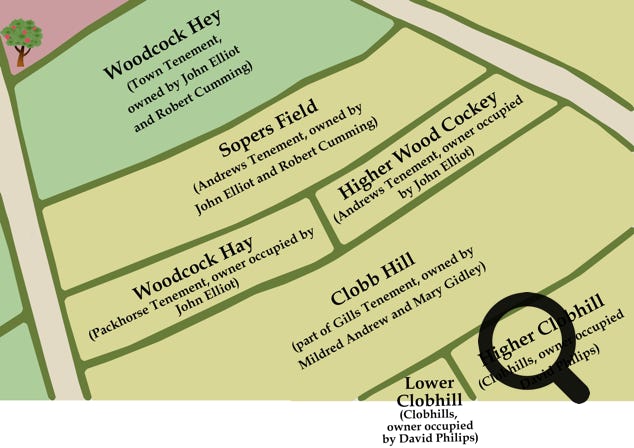

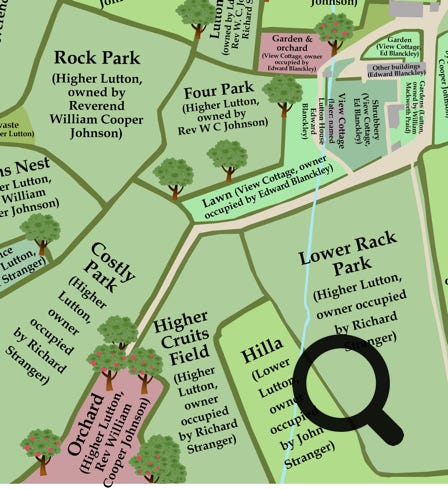

Illustrations are maps I drew from the to the apportionment data.

“Lord of the Rings” names

Names recorded in the cursive script of the parish’s tithe apportionment (the directory accompanying the map) feel heavy with the earthy scents of loam and green growth. Lord of the Rings enthusiasts might pick up a Tolkienesque feel:

- Coldish, Bow Down and Hambridge Marsh: Stippadon

- Great Gortley: Lower Lincombe

- Little Roundey and Higher Butter Park: East Wonton

- Lower Tangs: Higher Yelland

- Oaten Hill and two Skyhorns: Stidstone

- Parsons Underway and Little Drum Hill: Higher Lutton

- Pocket Apple Orchard, Bee Garden and Sparks Little Marsh: Weeks Horsebrook

- Sixpenny Plat: Binnamore

- Snow Downs: Harrell Water

- Sprigs Moor Field: Late Stidstones Tenement

- Three Corner Bottom, Goosepool Copse and Shapey: Didworthy

- Watery Lane: Kerswell

- Wheaty, Lower Greeney, Silver Hill and Sky Hill: Sopers Horsebrook

- Wool Wash Meadow: Charford

- Wrens Nest: Higher Lutton

- Yonder Brim Park, Goosey Plot and Crowdy Cross Field: Great Palstone

People’s names can feel equally fantastical:

- Faithful Blatchard

- Hercules Joint

- Quintin Hext

- Servington Savery

However, there’s much more to be found than these quaint, Tolkienesque names. Close scrutiny of the tithe map shows individual trees plotted beside hedges, and the place names recorded in its apportionment provide a staggering amount of information:

• The origin of modern street names

• A window into language formation

• Old Devon words

• Ancient Brentonians

• Suggested stories

• Class inequality

The origin of modern street names

Many modern street names match field names in the tithe map:

• Brakefield: Brake Field.

• Clobells: fields belonging to different farms with names like Clobb Hill and Lower Clobhill. One of the farms is called Clobhills. The rise of land modern-day Clobells occupies seems to have been known as Clob Hill.

• Chapel Fields: Chapel Field.

• Corn Park: Lower Corn Park and Upper Corn Park.

• Crowder Park: next to Crowdy Cross Park

• Green Fields: Higher Green Park.

• Higher Green: Higher Green Field

• Palstone Park: Little Palstone Park and Great Palstone Park

• Pool Park: Pool Park.

• Springfield Road: lies on the site of Sprigs Moor, and may have got its name from “sprig’s field”

• Woodhaye Close: Woodcock Hey.

A window into language formation

The tithe record contains “fossilised” examples of proper names developing from utilitarian descriptions. Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention.

“Where do you want me to plough?”

“Bottom field.”

Or

“Crooked meadow.”

Or

“Yonder little field.”

It can be hard to distinguish proper names from descriptions in the tithe apportionment. “Hedges”, “road” and “orchard” are clearly descriptions, but should the many “little orchard”s be capitalised?

“Crooked meadow” sounds like a name developed to distinguish it from other pieces of land.

“Pannells Meadow” definitely seems to include a proper name.

But what of the instances where places called “Meadow” are described as “Pasture”? In these cases, Meadow seems to be the pasture’s proper name telling the story of the land’s usage.

“Higher barn & court” in Weeks Horsebrook seems to be a combination of a proper name with a description (Higher Barn & court). Other entries, such as Little Bullcombe Park in Great Palstone, seem to include older descriptive names (in this case “Bull Combe” meaning bull valley) which had already become proper names. In other words, utilitarian descriptions evolved into proper names continued their evolution by forming newer names.

Old Devon words

• Brake: furze/bracken patches. E.g., plots named “Brake” in East & West Moore, Lisburne and West Wonton are have “furze” in the state of cultivation column.

• Close: field (see also Down and Park).

• Court: seems to be a courtyard/paved area.

• Down: field (see also Close and Park)

• Furze Pen: a field that’s presumably been formed by clearing furze/bracken. Examples include: Cross Furze Pen in Forder; Water Furze Pen & Wild Oak Furze Pen in Stidston; and Lower Furze Pen in Zeale.

• Linhay: according to Wikipedia, an ancient type of circular structure found in England, particularly associated with Devon, that’s characterised as a two-storeyed building with an open front, with a hay-loft above and livestock housing below.

• Mowplat: local dialect for Mowplot (see below)

• Mowplot: appears to be a Devon and Cornish word, possibly meaning to a hay field.

• Park: the most common name for fields in the tithe map (see also close, down). A member of South Brent Storytellers & Archive Facebook group said they’d heard that “parks” are fields that were created by joining strips of land, probably dating back to the end of the feudal system in the middle ages.

• Plat: seems to be plot rendered in the local accent. E.g.,“Little Plot”, “Higher Plat” and “Potato Plat” in Higher Lutton.

• Rack: “rock” in local dialect (there are seven “Rack Park”s and nine “Rock Park”s)

• Slade: uncertain meaning.

• Strole: may be places reached by a short walk.

• Tenement: farm (e.g., Sopers Tenement and Cranches Tenement)

• Waste: uncultivated land; evoking the mindset that land that didn’t benefit humans was wasted

Adjectives used in the 1841 tithe map include:

Great, little, middle, crooked, lower, higher, middle, square, three corner, tongue and homer (the opposite of yonder or outer (e.g., Homer Neale and Yonder Neale in Ley, and a farm at Over Brent has fields called Homer Beara Park and Outer Beara Park).

There’s Higher Abovetown, Middle Abovetown and Lower Abovetown in Higher Badworthy, and, in Kerry Down there’s Middle Park and Second Middle Park (evidently “middle park” was a popular description there).

According to an article on Martin Ebdon Maps’s website, the adjectives in South Brent’s tithe map tally with ones used in north Devon:

“The first word in a field-name is often an adjective, distinguishing a field from its neighbours by its compass direction (North or South, East or West, Easter or Wester), its size (Great or Little), its height (Higher or Lower), or its location relative to the farmstead (Home, Homer, Inner, and Hither all mean ‘near’ while Over, Outer, and Yonder mean ‘far’). Hence, there are pairs of fields that have the same basic name such as Western Barn Park and Eastern Barn Park, Higher Broom Close and Lower Broom Close, Great Down and Little Down, Home Four Acres and Outer Four Acres. Sometimes, in between such a pair of fields, there is a third one whose name begins with the word Middle. Very few field-names use the adjectives Big or Small; they are vastly outnumbered by names that begin with Great or Little.”

A PDF, entitled The Secret of Field Names, published by Archi UK Maps, says:

“Through my research I have found fields containing mounds to have names such as Mound Field, Coney Field, Moot Field, Barrow Field, Rounds and other similar names. In Cornwall fields containing the name 'Round' are often the sites of small Iron Age Celtic settlements. 'Coney' is the old word for rabbit.”

Having come across several South Brent fields with “coney” in their names, I was excited to check this out but, disappointingly, when I compared them to OS maps, there were no ancient burial mounds, etc marked. Ditto for Burrow Park in Burland, just north of Harbourneford.

Ancient Brentonians

The identity of previous land-users are “fossilised” in the 1841 tithe apportionment. These are people who lived in Brent decades, or even hundreds of years before the tithe map was recorded.

For example, in 1841, Sopers Horsebrook was owned by Henry Cutmore and tenanted by Peter Kingston (with no one by the name of Soper in the near vicinity). There’s also a Sopers Field in a farm called Andrews Tenement.

Other traces of ancient Brentonians include:

• Cranches Tenement

• Dicks Meadow: Higher Lutton

• Dukes & Peeps: Binnamore (with fields called Peeps and Lower Peeps

• Farmer Ned’s Field: Late Stidstones Tenement

• Nicks Plat: Lower Lincombe

• Nichols Tenement

• Quicks Field: Andrews Tenement

• Pannells and Pannells Meadow in Forder

• Peters Park: Great Over Brent

• Tuckers Free Field: Charford

• Whites Field: Town Tenement

• Wyatts Aish

The names of Lower Somer Hill and High Somer Hill in Stidston may be echoes of a previous Brentonian named Somer who also gave their name to Somerswood by Lydia Bridge.

Was Polly Meadow in Little Bulhornstone named after someone called Polly, or is “polly” an old, Devonian word?

Suggested stories

Some of the names recorded in the 1841 tithe map tell stories of changing land-use.

Field names containing “furze” are classed as pasture, whilst ones named meadow are classed as arable. Of the many plantations, almost all are described as “fir”, bar one in Binnamore that’s an orchard. More examples:

• Lisburne: “Nursery” is arable.

• Sopers Horsebrook: “Long Orchard” and “Lower Marsh” are arable.

• Barley Combe: “Potato Plat” is an orchard.

• Late Stidstones Tenement: “Orchard Plat” is arable.

Dramatic social stories are hinted at too:

• Cost is Cost: Lower Badworthy.

• Duels Field: Kerswell.

• Grants Castle & garden: Lisburne.

• Stabs Field: Binnamore.

Land ownership and class inequality

Tenants of one farm were sometimes the owners of another. For example, Quintin Hext owned Higher Badworthy; rented Binnicknowle from James Cornish and co-owned “Part of Binnicknowle” with James Cornish

A select few, such as Lady Elizabeth Carew, owned multiple farms, and tenants, like John Manning, lived in homesteads described as “dwelling house, other buildings, yard &c”; but lowlier people live in cottages where a single occupant’s name makes do for the tenants:

• Barrack Street: James Hannaford and others

• Binnicknowle Cottages: Henry Hannaford and others

• Church Street: Sarah Smerdon and others

• Harbourneford: Robert Tucker and others.

• Splatton: Edward Leaman and others.

• Sprigs Moor: John Wakeham and others

Conclusion

The field names listed in South Brent’s 1841 tithe apportionment are a treasure trove of historical information. This includes the origin of modern street names (e.g., Clobells comes from “Clob Hills”); a window into language formation (e.g., Little Bullcombe Park); a record of old Devon words (e.g., Higher Plat) and ancient Brentonians (e.g., Cranches Tenement); suggested stories (such as Duels Field in Kerswell) and traces of class inequality (e.g., only Edward Leaman’s name was given for the five households at Splatton).