Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact | Facebook

Nelson’s Descendants in Brent

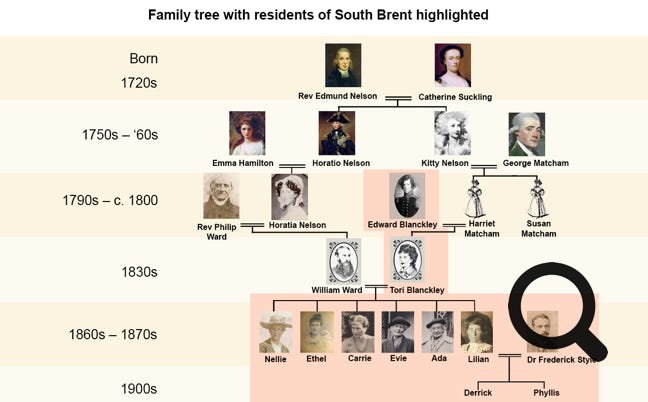

Lord Nelson’s only descendants come through his famous love affair with Emma, Lady Hamilton. Six of their great-grandchildren lived quietly in the south Devon village of South Brent from the prime of their lives until their little-noticed deaths. Only the youngest married, and their line was all but forgotten.

As a descendant of Emma & Nelson’s South Brent line, I’ll explain why Nelson’s great-granddaughters left suburban London for sleepy South Brent, and what they did there.

Exhaustive research combined with family stories have revealed three key drivers behind their move: Nelson’s dying wish being ignored; his nephew-in-law buying a cottage overlooking South Brent; and his niece retreating after a string of tragedies. The family tree (above) shows that the six sisters – Nellie, Ethel, Carrie, Evie, Ada and Lilian – were Nelson & Emma Hamilton’s great-granddaughter’s through their father, William Ward, and also the great-granddaughters of Nelson’s sister, Kitty Matcham, through their mother, Tori.

The story starts in the late 1700s when Emma and Nelson met in Naples. Many people still view Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson as Britain's greatest hero more than 200 years after his death at Trafalgar, on 21st October 1805. His victory against the combined French and Spanish navies enabled the British Empire to spread across the globe with no one to stop them.

However, few people know that his famous lover, Emma, Lady Hamilton, had been an international superstar before Nelson's own rise to fame. Despite being born to a Cheshire mine’s blacksmith in 1765, during an era of rigid class structure which allowed no social mobility, especially for females, Emma, Lady Hamilton had been the most painted woman in Europe, responsible for the “Jane Austen” Regency fashion revolution, called “à la Emma” at the time. Her teenaged success in learning upperclass deportment inspired the musical, My Fair Lady. As wife of the elderly British Ambassador to Naples, Sir William Hamilton, she became best friends with the Queen, who she persuaded to release supplies Nelson needed to chase Napoleon’s fleet to Egypt, where he became a superstar for his victory at the Nile on 1st August 1798.

Lord Nelson and Emma, Lady Hamilton's only child was born in late January 1801. They named her Horatia. Illegitimacy was deeply frowned upon, and the couple sought to disguise their relationship, so they pretended they’d adopted the baby from a crewman of Nelson’s named Thompson. They further concealed Horatia's parentage by pretending she’d been born in October 1800 (three months before her actual birth) whilst they’d been travelling, very publicly, across Europe. Nelson’s naval career kept him away at sea for the majority of Horatia’s early years. He wrote affectionate letters to both her and Emma. He asked Emma to find, and purchase, a country home for them to share. She bought a property called Merton Place, south of London, in 1801. Nelson’s siblings were frequent visitors, and when Nelson was finally allowed home-leave to visit it himself, he named it “Paradise Merton”.

Nelson – as national hero and a man – later felt able to acknowledge paternity of Horatia, but Lady Hamilton had to keep her maternity secret because, otherwise, sexist society would have spurned both her and Horatia. Georgian and Victorian society hated strong women, especially ones who were low-born. They did everything they could to discredit Emma’s achievements so she was remembered only, unfavourably, as Lord Nelson’s mistress, and her astonishing achievements were deleted from the history books. There’s evidence Emma and Nelson’s own grandsons bought into the hate campaign against her.

Nelson’s dying wish wasn’t for his funeral to be the biggest public event London had ever seen. Nor was it to have a square in central London renamed “Trafalgar” after his place of death, with a massive column in the middle for his lonely statue to balance on. The only thing he'd actually asked for was for the wife of his heart, Emma, Lady Hamilton, to receive a government pension for her own war contributions. In an earlier codicil to his will, he’d asked for provision to be made for their child, Horatia, too. Did the government honour this? No, they did not. They didn’t even permit Emma to attend Nelson’s funeral. Nelson’s siblings all received generous grants, as did his estranged wife, Fanny. Emma had powerful allies, including the Prince Regent and two of his brothers. She squandered money she didn't have entertaining them and other allies.

Mounting debts forced Emma to flee England with teenaged Horatia in the summer of 1814. They took a boat from London, instead of Dover, because the quay was less likely to be watched by creditors. This made the journey much longer. Horatia suffered badly from sea sickness, but Emma was optimistic that everything would now be OK. Sadly, it wasn’t. Emma died in rented rooms in Calais, on 15th January 1815, with only Horatia by her side.

Horatia was adopted into the family of Nelson’s sister, Kitty Matcham. George and Kitty Matcham began a tour of post-war Europe in 1816 with their friends, the Blanckleys, and their many daughters. Young Harriet Matcham married Edward Blanckley in Naples in April 1819.

Edward Blanckley was promoted to Royal Navy commander, and led an expedition circumnavigating South America in the early 1830s. He contracted a lingering tropical illness during the trip, but returned to Portsmouth in 1834 with lots of booty. He joined Harriet in their fashionable new-build home on Plymouth’s Union Road (now called Union Street). Their daughter, Tori, – full name: Catherine Nelson Parker Toriana Blanckley – was born there in 1835. Edward Blanckley purchased and extended a country home, called View Cottage, on the hill overlooking the south Devon village of South Brent. It’s likely the house was a clean-air retreat to aid his health. The 1838 tithe map lists him as owner and occupier of View Cottage.

Edward Blanckley’s wife, Harriet, died of childbed fever in Raleigh House, Plymouth, on 19th August 1838. The infant boy (named Nelson Raleigh Matcham Blanckley) survived, however, and was adopted, along with three-year-old Tori, by Susan Moore, Harriet’s widowed sister. Susan had married a wealthy landowner, named Alexander James Montgomery Moore, in 1832, only to be widowed in 1837, aged thirty-four, with two small sons, Alexander and Acheson.

There’s no record of Susan staying with Harriet in Lutton House, or Plymouth, after her husband’s death. But it seems likely that she was there because she had Harriet’s baby with her in Worthing, Sussex, six-months after Harriet died. Childbed fever would have been a horrific death for Susan to have witnessed.

Susan was with her young charges in Worthing in early 1839, likely because it was a health spa. Four-year old Acheson died there on 18th January 1839 of typhus. Then, Harriet’s six-month old baby died from convulsions on 15th February.

Regardless of any grief, Susan still had her five-year-old son, Alexander, and three-year-old Tori to care for. The 1841 census shows them in a tiny house near to (but not in) her eldest brother’s mansion in Wiltshire. Alexander embarked on a glittering military career when he was fifteen – he was briefly governor of Canada in later years – but census records show Susan bringing Tori up in nomadic, social isolation.

Returning to Horatia, we can never know what she knew privately. However, if she’d known that Emma was her mother, admitting to it would have caused society to spurn her. Society had accepted her as Lord Nelson’s illegitimate daughter because Nelson was a man and viewed as a national hero, so blood from him could only be good. But society had quickly come to hate Lady Hamilton, and they’d never accept Horatia if they thought she had her mother’s blood. Georgian and Victorian society believed criminal types had “bad blood” that was passed to their children. Illegitimate babies were spurned because it was believed that their mothers, who were viewed as lacking all morality, passed their “bad blood” to them.

Horatia had left the Matchams merry European tour before Edward Blanckley married Harriet Matcham in Naples. Probably not in a partying mood after Emma’s long decline and death, she had opted to stay with the family of Nelson’s other sister, Susannah Bolton, in the northern Norfolk village of Burnham Westgate. She married the village’s young curate, Philip Ward, on 18th February 1822. Philip was made vicar of Tenterden in Kent in 1830, just after the birth of their son, William George Ward. Susan Matcham was William’s godmother. Horatia biographer, Winifred Gérin, noted that, of all the Matchams, Susan maintained the closest, longest-term contact with Horatia. Susan was, therefore, likely to have visited Horatia and her family in the vicarage in Tenterden with young Tori.

Philip Ward’s clerical salary was stretched by financial problems inherited with his Tenterden posting. He home educated his five sons, but financing further education was problematic. Their firstborn, Horatio Nelson Ward; and third son, Nelson Ward, had started training for the clergy and law. But prospects for their other boys were uncertain.

Horatia’s rural vicar’s wife obscurity was shattered when Dr T J Pettigrew’s Memoirs of the Life of Vice-Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson was published in 1849. Pettigrew had been employed in the household of the philanthropic Duke of Sussex, Prince Augustus Frederick, who’d died in 1843. The Duke of Sussex had been Queen Victoria’s favourite uncle, as well as one of the few people who’d staunchly supported Emma after Nelson's death. Pettigrew’s book contained previously unseen transcriptions of Emma & Nelson’s correspondence, which, he said, proved Horatia’s parents were Nelson and Emma. This went ‘viral’ in the newspapers of the day. In a letter to The Times, Horatia denied Emma was her mother, but Pettigrew retorted that he had more letters he could publish if she saw fit to argue. Thankfully for Horatia, the viral attention turned to the fact that Nelson’s dying wish had been ignored. A group of well-wishers launched an appeal nicknamed “the Horatia fund” on 8th May 1850. Horatia requested that the money raised was used to finance careers for her other three sons, Marmaduke, William and Philip. Marmaduke gained a career as a naval surgeon, and the younger lads were granted East India Company cadetships.

When Horatia was widowed in 1859, her lawyer son, Nelson, urged her to move near to him in the suburb of Pinner, seventeen miles north-west of London. They lived in a leafy, new-build estate called Woodridings, which had been home to the famous Isabella Beeton, author of Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management.

Very unfortunately, Horatia’s youngest sons, William and Philip, succumbed to major liver illness in the subcontinental heat. Philip, presumably home on sick-leave, died from the disease in Pinner in 1864. Liver illness later killed William too. Ironically, Nelson had urged his brother-in-law, George Matcham, to bar his sons from joining the military because he wanted them to live long lives. If Nelson’s dying wish had originally been honoured, Horatia would have been comfortably off and able to finance non-military careers for her children. As it was, the “Horatia fund", in seeking to belatedly honour Nelson’s dying wish, caused two of his grandsons to die in military service.

In the same year that Philip died – 1864 – William returned to England on twenty months sick-leave granted because of liver illness. He married his second-cousin, Tori, in Clevedon, Somerset, in November 1864. He took Tori back to India with him, where they settled in the British cantonment at Jaulnah, inland from modern Mumbai on the high plateau. Apart from the intense heat, life for British families was comfortable there. There was a racket court, theatre, schoolhouse and post office. Tori bore William five daughters in Jaulnah between 1865 and 1871. These are the girls who ended their lives quietly in South Brent.

William, Tori and their five little girls sailed back to England on the P&O steamship, SS Delta. Naval & Military Gazette reported their arrival in Southampton on 30th April 1872 as “Major and Mrs. W. G. Ward, five children and servant”. Their servant was almost certainly an ayah (Indian nanny). The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had shortened the journey from India to England by 4,500 miles. This resulted in a flood of British families, like William’s, travelling back to England with their ayahs. Sadly, many of these ayahs were then sacked and had no money to pay for tickets home. Britain was so flooded with destitute ayahs that an Ayahs’ Home was opened circa 1891.

William and Tori moved into a house near Horatia in Woodridings. Their sixth child, Alice Lilian Ward, was born there on 15th July 1873. William left his family and arrived back in Madras in January 1874. He was promoted to Lieut. Col on 10th February 1877. On 7th January 1878 he was granted furlough to return to England for “private affairs”. It’s not clear if William’s “furlough” was actually sick leave and the date of his arrival in England is elusive. However, he was in Hastings, Sussex, in early August 1878. According to biographer, Gérin, Hastings had been Horatia’s favourite health spa.

The three key drivers, named at the start of the article, now kick into swift action. Firstly, William had joined the military because of the key of Nelson’s dying wishing being ignored. On 10th August 1878, he’d been suffering “congestion of liver” for four months and diarrhoea for 21 days. He died in a guesthouse overlooking the English Channel, and was buried in Hastings cemetery on 14th August.

Secondly, the key driver of Nelsons’ niece – Susan – retreating after tragedy, clicked in when Tori followed the pattern Susan had reared her with, and fled Pinner. Four months after William’s death, on 12th December, when his will was proved, her address was 15 Alexandra Road, Upper Norwood, Surrey. This was on the other side of London from Horatia in Pinner, but only 500 feet from her aunt Susan in Gipsy Lodge, Gipsy Hill.

It wasn’t long after Susan’s death in 1885 that the third key was activated: Nelson’s nephew-in-law buying a cottage overlooking South Brent. View Cottage, which Edward Blanckley purchased in the mid-1830s, had been let to a succession of tenants. The last, Giles Daubney, vacated Lutton House – as View Cottage was now known – in 1888. The 1891 census shows Lutton House unoccupied, and Tori and her six unmarried daughters in a house in Torquay. However, Lutton House was extended around this time, and, in July of the same year, according to Western Morning News, Tori’s daughters, Nellie and Ada, performed in ‘an interesting entertainment’ arranged by South Brent’s vicar, Rev Speare-Cole. This suggests they’d been living in the community for some time.

Tori’s daughters performed in a variety of village shows during the 1890s, including an October 1893 concert & operetta reported by Totnes Weekly Times, which lists all the sisters (bar Carrie):

“A Dress Rehearsal,” was exceedingly well staged, being performed entirely by the ladies, and was admirably rendered… [the cast included] Miss L. Ward ; Clara Wilkins (afterwards the Prince), Miss E. Ward ; Martha Higgins and Carry Jackson (afterwards the spiteful sisters)… Miss A. Ward ; Sophonisba Spivins (Romantic Girl), Miss E. H. Ward ; Miss Prudence Pichbeck (a Visitor)… Miss N. Ward ; Servant, Miss R. Foster.

The Ward sisters – Nelson’s great-granddaughters in South Brent – were actively concerned for animal welfare. Totnes Weekly Times’s October 1893 report of prosecutions of animal abusers at South Brent fair noted, “Miss Ethel Ward, of South Brent, deposed she complained to the Inspector of the cruel beating of ponies.”

When my mum spent her school holidays at Lutton House in the 1950s with the surviving sisters, Evie and Ada, they had an anti-vivisection leaflet pinned up in the bathroom and were vegetarians (although they ate chicken). This is my mum’s account of what her father told her:

“Derrick said the aunts had no sense of taste whatsoever. Marmite in everything (scrambled eggs, etc). Soup: vegetable water flavoured with Marmite and thickened with tapioca: could have been worse, wasn't that bad. But wasn't yummy yummy, I want to have more.”

They kept chickens in repurposed “cat houses” – large outdoor hutches – which had presumably been erected to accommodate some of the nine, highly-territorial cats my mum was told they’d kept. Ada boiled up vegetable peelings every evening to make hen-food. If it was bad weather, Ada donned an ancient Victorian bonnet when she went out to feed them.

Tori, for her part, had been driven by concern for the well-being of South Brent’s poorer residents. In those pre-NHS days, good health-care was hard to access for people on low incomes. Dr Parson's 1881 report of the prevalence of typhoid fever in South Brent reveals living conditions to have been very unsanitary:

Privy accommodation is scanty, one privy being sometimes shared by five, six, or seven houses. In such cases either the privy is allowed to get into a filthy condition, through disputes as to the responsibility for its cleanliness, or else it is not made use of, the men resorting to the fields, the women using utensils in the house, and throwing the contents of them on dung heaps.

A number of cases of typhoid fever occurred in 1877, in a group of wretched cottages in Fore Street, and behind the “ Anchor ” inn. One of these, then inhabited by a man, his wife, and 10 children, but now empty…The lower floor, of rough stone, is below the ground level ; the bedrooms are only 6 ft. 6 in. high to the roof, which is not ceiled, but merely plastered on the under side of the slates, and does not keep out the rain…There are no back windows, and the front of the house looks into a narrow passage, bounded by a high wall… Close to this are six back-to-back houses, in two of which fever occurred about the same time … at one house the window of the kitchen opened into a slaughter-house, and that immediately under the windows of the public meeting room of the village a huge heap of pig’s dung was piled…

Tori teamed up with fellow residents, including the village’s first GP, Dr Frederick Style, to form South Brent Nursing Association in October 1901. Their first meeting was held on 10th December that year and, according to Totnes Weekly Times (see highlighted clipping below) was attended by Mrs. Ward and a Miss Ward who, as no initial is given, was probably Tori’s eldest, Nellie. Both Dr Style and Tori were voted onto the new committee.

South Brent Nursing Association

––––––––––––––

This useful association has been in existence for about two months… present at the meeting… Mrs. Ward, Miss Symons, Miss Ward, Mrs. Mahon, Misses Mahon, Mrs. Mitchell, Miss May, Miss B. May, Mrs. M. J. Codd and Mrs. Pearse, Messrs. Collins, Crimp, Hill, Hawke, Gill, Mr. and Mrs. Hull, etc. Mr. J. R. T. Kingwell was voted to chair, and the following were elected by ballot to form the new committee :–– Mr. W. H. Hawke 24 votes, Dr. Style 23, Mrs. Collier 20, Mrs. Speare-Cole 18, Mrs. Ward 18, Mr. R. H. Gill 17, Mr. S. H. Hill 17, and Mrs. Mahon 16… Dr. Style agreed to carry out the secretaryship until an appointment could be made. It was decided to make the appointment of treasurer at the next general meeting fixed for 4 p.m. on Friday December 20th. Notice was given that at that meeting the whole rules of the association would be revised, but it was recommended that the newly-appointed committee should first go over the rules.

Of Tori’s six daughters, only the youngest, Lilian, married. She wed Dr Frederick Style in St. Petroc’s church, South Brent, on 24th June 1903. In Exeter and Plymouth Gazette’s report of their wedding, Frederick is praised for “splendid tact and ability in connexion with public functions. South Brent Choral Society owe him principally for its success…” Lilian is noted as “equally popular among the poor of the neighbourhood, being a member of a family who has always shown a keen interest in the poor.” My grandfather told my mum that Frederick Style sent the Ward sisters out to deliver beef tea to sick people on low incomes.

Frederick Style ran his GP practice from their family home, Windward. Not to be confused with the modern nursing home named Windward, their home was one of the buildings on present-day Chapel Fields that overlooks the new school playground.

Their first child, Derrick William Graham Style – my grandfather – was born on 21st April 1904. Their second child, Phyllis Horatia Style, was born on 14th March 1907.

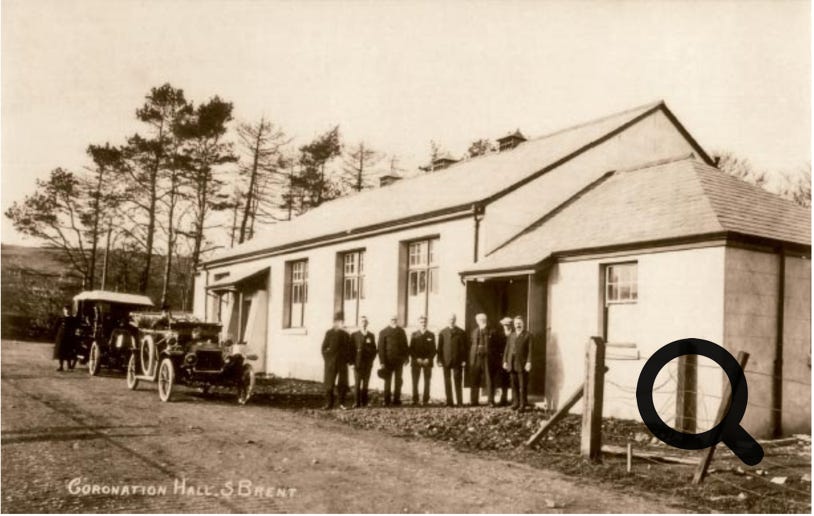

Frederick Style was on the committee for the village’s new church hall opened in February 1912. The photo below shows it at about the time of its opening.

South Brent’s new hall was named Coronation Hall for George V's coronation, on 22nd June 1911. However, the hall wasn’t officially opened until 13th February 1912. According to Western Times, the hall had been completed about six months prior to its official opening. No reason is given for the six-month delay, but it may have been because the wife of committee member, Dr Style, had died on 4th August 1911. Our family story is that Frederick’s wife, Lilian, had died of a weak heart whilst pregnant. Her death certificate confirms that heart failure killed her.

According to my mum, after Lilian’s death, Derrick and Phyllis (aged seven and four), ‘stayed at Windward and Carrie moved in with them. She took responsibility for raising them and I think both Derrick and Phyllis’ intolerance of the Aunts came from their father, who, reportedly, couldn’t stand having her around him.’

Derrick wasn’t kind to his little sister, Phyllis. He bullied her in cruel ways. For example, slowly pulling hairs out of her forearm. Their father, Frederick, sent Derrick to college at Epsom, but Phyllis was sent to a small dames’ school in Mutley, Plymouth.

According to my mum, Frederick, being a rural GP, needed quick transport, and:

‘the man, I forget his first name, who founded Soper’s Garage in South Brent had started out working for my grandfather (Frederick) as a boy to travel with him in his car. Frederick had one of the first motorcars in the south-west. It used to break down a lot, so the boy learnt about mechanics.’

Also:

‘Frederick was notorious in that if a car came the other way, THEY had to back, even if he’d only just entered that stretch and the other car had to back for a long distance.’

Petrol costs soared during World War 1. This was such a major problem for rural GPs that British Medical Journal’s August 1916 issue featured ‘Motor Notes for Medical Men’. Frederick was a contributor:

PRACTICAL EXPERIENCE OF PARAFFIN.

SIR,—It may possibly interest Ford car owners to know that three months ago I fitted a " superheater " to my car, which has enabled me to run on pure ordinary lamp oil at ls. a gallon, and that the car runs in every respect as well as it did on petrol.

The total cost of superheater, together with cost of fitting and of certain alterations I made, amounted to £6 18s. 6d. The mileage with paraffin is the same as with petrol, so that using, say, 30 gallons a month and allowing for a small quantity of petrol for starting, etc., the " super-heater " pays for itself in less than three months, whilst the annual saving works out at about £30.

As sent out by the makers, the superheater was provided with a glass reservoir, connected with inlet pipe. This had to be filled with petrol each time one wished to start up. Finding this a nuisance, and extravagant with petrol, I discarded it, and had an auxiliary petrol tank fitted. By means of a three-way tap, worked by a lever near the driver, having started upon petrol, one turns off the latter after a few minutes and gets on to paraffin without any trouble.

Naturally there are certain drawbacks to the use of paraffin. So far as my experience goes they are as follows:

(a) The piston heads require cleaning more frequently; I have had mine done three times. On a Ford this is not a very difficult job.

(b) Inability to restart without injecting petrol after the superheater has cooled down. This is not a very serious draw-back, as petrol can easily be injected through a tap on the inlet pipe end a teaspoonful is sufficient. In the event of a lengthy stop, in order to avoid trouble in restarting, I turn off paraffin a few minutes before stopping the engine and get on to petrol, so that the carburetter is full of the latter when I wish to start up again.

When first installed I did not get quite such good results as I am now getting. There is a certain difference in driving on paraffin, but after a few weeks’ experience one notices no difference whatever.—I am, etc., South Brent, Devon, Aug.1st. F. W. STYLE.

Derrick had a private education at Epsom and went on to become a chemistry professor in King’s College London, but Phyllis remained living in Windward with her father and Carrie. My mum recalls:

‘Phyllis did once tell me that [her aunts] used to tell her she was ugly - so that she didn't grow up vain! (Surely not all of them; I can't speak for the rest of them but I can't believe that Ada would ever have said such a thing)…

…According to a reliable source, Frederick’s partner in the surgery warned him that Phyllis would have a breakdown if he didn’t allow her a bit of freedom to make a life for herself. His reply: “her place is at home”.’

Phyllis, aged twenty two, was admitted to Wonford House, a mental asylum near Exeter, on 18th September 1929, eighteen months after Tori’s death. Her medical records, held by South West Archives, show her admittance was authorised by her father. The following is noted under ‘History of Present Illness’:

‘Has always been shy, and solitary. About fourteen months ago she had an attack of acute excitement… lately she became suspicious… she was “influenced” by her dead mother and auditory hallucinations were present.’

It’s easy to assume that Frederick had cast his daughter away without a care, simply because she was difficult, but Phyllis’s writing case – which my mum passed to me – contains letters from her aunts at Lutton House, and this one from Frederick, dated 14th March 1932 (check out his phone number of ‘S. Brent 7’!):

‘My darling Phyllis,

I am so sorry that I quite forgot your Birthday but you know how I am about remembering or rather not remembering dates etc so please forgive me & accept my warmest & best wishes for the Day with the enclosed little pin, which I got when in Plymouth this afternoon.

Let me know how you are & if you would like us to come over [to] see you one afternoon?’

On the back of the letter, Frederick wrote:

‘With love from your loving Daddy’

Dr Frederick Style died on Boxing Day less than two years later. According to Western Morning News and Daily Gazette (30th December 1933), his funeral was well-attended, and ‘Family mourners were Mr. D. W. G. Style (son), and the Misses Nelly, Evelyn and Ada Ward (sisters-in law).’

Despite having attended his father’s funeral, Derrick cut himself off from South Brent. He married his London housemate, Lilian ‘Koka’ Langford, during World War 2. According to my mum, it was Koka who instigated Phyllis’s release from Wonford House on 12th June 1946. It may well have also been Koka’s influence that caused Derrick to arrive unannounced at Lutton House, much to his aunts’ surprise, with a wife and toddler daughter (my mum). In her words:

‘The Aunts greeted us enthusiastically rather than noisily - but with delighted laughter. A bit later on, Ethel took me down to the bottom of the orchard. We must have collected a flower pot and a trowel on the way, as once there she picked out a fallen pine cone and showed me how to fill the pot with soil and stick the cone into it. At that moment I felt at home.’

Although my mum only met Ethel when she was very young, she spent her school holidays at Lutton House with Evie and Ada. I grew up with stories of ‘the little, old ladies’ who lived in Lutton House before my beloved grandfather (Derrick) took up residence.

My mum treasured a pair of saucers, one pink and one blue, which had belonged to them. She said Ada ‘had blue sheets, blue china (whereas Evie had pink sheets and china).’

Sadly, both saucers were smashed and lost long ago. When I last visited my mum, I was, happily surprised when she showed me a yellow saucer had come from Lutton House. I commented that I’d thought all their saucers had been pink or blue, but she told me that the yellow crockery had been for guests.

Of Tori’s six daughters – Nelson’s great-granddaughters in South Brent – Evie and Ada survived the longest. Evie died in Lutton House on 16th March 1961, and Ada, on 1st November 1965.

They were buried alongside Ethel in a flat-topped grave in South Brent cemetery, close to Nellie and Carrie’s almost identical grave. Nelson isn’t named on either tomb, but their father, William George Ward, is. Similarly, Tori was buried with her long-dead husband, William George Ward, in Hastings, with no mention of Lord Nelson. The tomb Evie and Ada are buried under, next to Ethel, states:

IN LOVING MEMORY OF ETHEL MARY WARD DAUGHTER OF LIEUT. COLONEL W.G. WARD MADRAS STATE CORPS DIED DEC. 25. 1946.