Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact | Facebook

George Matcham (1753–1833):

A Biography of Lord Nelson’s Inventor

Brother-in-law

(First published in the Trafalgar Chronicle in 2022)

George Matcham was born on 30th November 1753 in Britain’s fortified colony at Bombay. He achieved adulthood with a single lung, and adventurous spirit. When his restlessness was stilled through happy marriage to Lord Nelson’s youngest sister, his lively curiosity turned to sedate problem-solving and resulted in him patenting two inventions of benefit to the Royal Navy. Although there are frequent mentions of him in biographies of Nelson and Lady Hamilton, no biography has so far focused on George himself.

Bombay had been under British control for the best part of a century. The island was a fortified garrison which the East India Company rented from the British monarchy for £10 a year. A 1754 watercolour depicts the fortified island as predominantly rural. Rolling, scrub-covered hills rise behind blocky European buildings clustering the shore. A two-storey grey-stone warehouse dominates the left-hand side of the image with a pier protruding into the sea. Behind it peeks St. Thomas Cathedral looking every bit like an English, rural parish church. A red-roofed building beside it is likely the theatre.

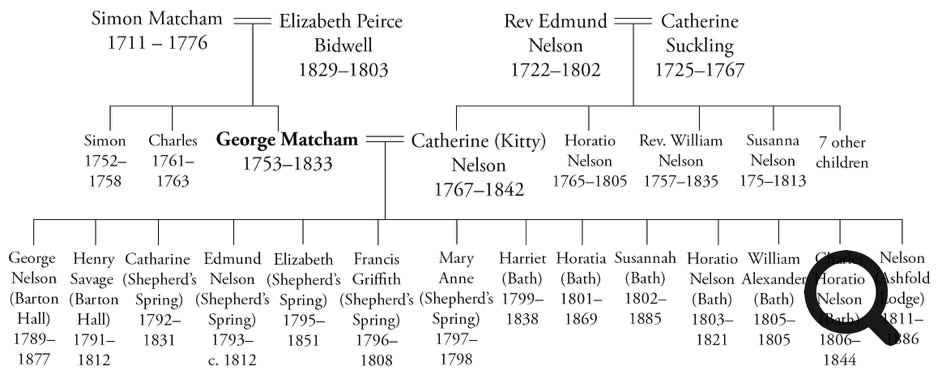

George's parents had been born in England. His mother, Elizabeth Peirce Bidwell came from a devout Presbyterian family. Her father had been lured to Bombay by job opportunities in the predominantly Presbyterian East India Company. She wed Captain Simon Matcham in 1751. They named their first child Simon, and George was born soon after. Elizabeth filled their garrison home with exotic nick-nacks and her husband brought home equally exotic tales from his patrols of the Indian Ocean. One being frequent sightings of shoaling mermaids with long, glossy hair, pug noses and fins in place of forearms, which were hacked up by Mombasa fishermen and tasted like fishy pork.

The Matcham brothers are described as ‘pasty-faced’ in a pair of Indian miniature portraits depicting them in ‘precocious dress of velvet coat, laced waistcoat, frills and velvet ribbon...’ Simon died aged six. A second brother, Charles, baptised in ’61, only lived until two. No causes of death are recorded, but contemporary travelers reported ‘deadly illnesses in Bombay’

George was sent to board at Charterhouse, near Smithfield in London. He was a fee-paying boarder in the house of the headmaster. The school’s archives hold no record of his arrival, though boarders as young as eight were admitted. Their records, however, tell us he left in December 1769. He spent a year in the East India Company's graduate school in Haileybury, Hertfordshire, and joined the Company as a Senior Merchant in ‘71. This was the highest rank in their commercial service (the hierarchy being Senior Merchant, Junior Merchant, Factor, Writer). The East India Company, whose original name had been the ‘Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East-Indies’ was at heart a merchants’ club with its private militia. Their 1757 victory at Plassey over the allied native and French forces paved their way for domination of Bengal. When the Mughal emperor ceded to them in 1765, the East India Company became ‘the effective rulers of Bengal. An international corporation was transforming itself into an aggressive colonial power.’

George was one of fifty-eight senior merchants listed in Bombay in 1771. Part of their remit was the administration of outlying factories (trading offices) in places such as Surat (the most important port for exporting textiles from Gujarat, north of Bombay). A contemporary account from Bengal tells of a lowly free merchant rising to Resident (governor) within ten-years. George, however, didn’t need to work his way up the ranks. The East India Company was not a meritocracy, and posts were awarded on a ‘who you knew’ basis. His father had been promoted to 'Master Attendant of the Honble [sic] Company’s Marine Officers’ by 1765 and eighteen-year-old George was ‘known’ to the right people when he graduated from their school in England. He was quickly made their resident at Baroche [Bharuch] charged with ensuring the profitability of native calico production, which required the hard labour of thousands of locals. Though young and privileged, George was deeply moved by ‘the misery of the people, and waste of fine agricultural land’ and filled journals with ambitious improvement plans.

His father’s career peeked in 1774 when, aged sixty-four, he was made Superintendent Marine of the Honourable East India Company (the equivalent of Admiral) and Senior Member of the Council of Bombay. Simon Matcham had little time to enjoy these pinnacles of Company success for he was buried in Bombay on 22nd June 1776. George’s widowed mother set sail for England in the next year never to return. Her journey via the Cape of Good Hope would have taken six-months.

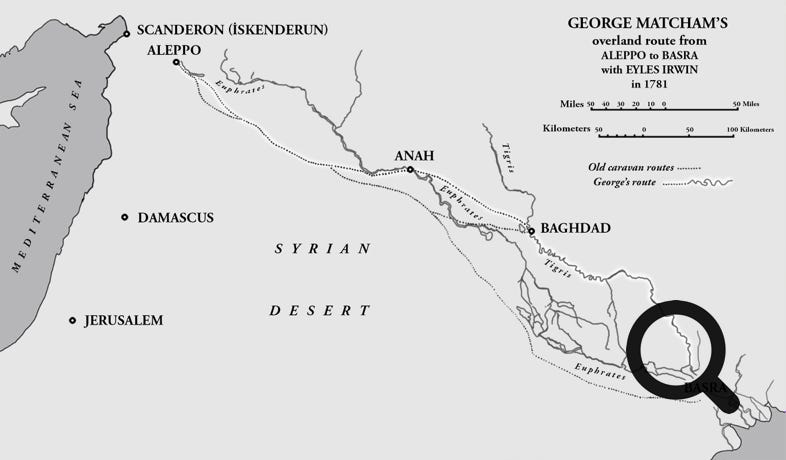

Twenty-three-year-old George decided to follow the overland caravan trail from Basra to Aleppo instead. The route was of keen interest to the East India Company, who wanted to transport merchandise and communication as swiftly as possible between Asia and England. There’d been several British expeditions to explore the route already that century. George’s decision to attempt it in 1777 coincided with the Company’s increased interest in further exploration. James Capper, who travelled the route from west to east in 1778, published “various land and sea-routes to India, with their qualifications.” Lieut. Samuel Evers led a party in ’79. And in 1780, Eyles Irwin, an Irish poet two years older than George ‘of the Madras... rode from Aleppo to Ana, and thence passed to Baghdad, Basra and India’ in the company of several Englishmen, of whom one was George Matcham.

George’s friends were horrified by his intention to travel overland because he was seriously ill with a damaged lung, but a doctor pronounced his health already so bad it would make no difference if went. George indeed went, and, in his own words, was ‘compelled to ride on untam’d horses at a rate of sixty or seventy miles a day, sometimes exposed to a burning sun, sometimes to the cutting air of the mountains, and often obliged to sleep in the open air.’ He had a small Persian rug to sleep on and subsisted entirely on mare’s milk. These privations apparently agreed with him for his lung healed during the journey (although it never entirely recovered).

The East India Company’s cordial relations with the Iraqi port of Basra were lost between 1773 and ’79 because of plague and Persian occupation. So, it’s unlikely George landed there in ’77. Detouring into Egypt, he was dismayed to find “the wretched Egyptians… sadly oppressed by an aristocracy, and there is no security in the Government.” The ruins of Alexandria caused him to reflect “We cannot sufficiently regret these despicable tyrants chacing [sic] away from this happy country the arts, sciences and commerce ; for what it still remains of the latter may be compared to the sweeping of a great warehouse, their merchants couldn’t even raise enough money to purchase the Italian cargoes…” He enjoyed visiting Egyptian merchants on donkey back (horses being prohibited to Christians). He then dawdled his way through Europe, where he studied ‘the height of civilisation in contrast to the East’, before joining his mother in her county home at Charlton Place, near Canterbury in Kent. He toured England and Ireland, making Indian-style sketches ‘for his mother’s amusement’, and wrote pragmatically to friends, ‘if the bulk of our fortune should come home safe, I mean to buy an estate jointly with my mother. I shall then marry and have three principal sources of amusement ; my wife, farming and hunting. If our fortune should not be happily remitted, I must again betake myself to Bombay.’

He wrote to his mother from Brussels at the start of his second overland journey in September 1780. Irwin’s account helpfully describes his journey as well as his own. On 11th March 1781, Irwin was surprised to be joined in Aleppo by “Mr. Matcham... whom we had left at Venice, looking for a passage to Scanderon [İskenderun, south-east Turkey]”. They departed the comforts of Aleppo on 19th March 1781 with a party of Arab guides... but after five hours, they’d travelled only thirteen miles. Their camels’ slow pace of “two and a half miles an hour” frustrated Irwin, George and their friend, Smyth, who found horses and “rode the whole stage”. Their route loosely followed the course of the Euphrates, which provided vital drinking water. On the morning of 2nd April, exactly two weeks after departing Aleppo, the party passed an abundance of ancient, riverside aqueducts as they approached Anah. The ancient city was in a sorry state with “forsaken mosques and towers …a broken bridge and surrounding ruins.” Food there, however, was sumptuous: “good mutton and fish, which were carp from the Euphrates, of a size, that, perhaps, no table in Europe could boast. The milk was excellent, and fruit was brought to us in abundance.” Irwin calculated that Anah was exactly three hundred and thirty-eight miles from Aleppo.”

A week, and two-hundred miles later, they at last approached Bagdad. “Messieurs Smyth, Matcham and myself remounted our horses, and, accompanied by our servants and seven Arabs well-armed, we bid our friends adieu, and pushed on for the city, in order to hasten preparations for our journey down the Tygris… What crowned our satisfaction, on having so happily finished our arduous journey by land, was to find from our host that a boat was engaged to carry us directly to Busrah [sic], but “Rude materials and ruder workmanship marked the only vessel in Bagdad, that was to be procured for money…” Baghdad comprised “narrow and dirty streets, ill-built and worse designed houses, deserted market-places, with more than half the city lying level with the ground…” The party languished until 21st April. Their Tigris voyage was frequently delayed by hostile tribes they evaded by lying low. Irwin left George at Basra on 7th May, waiting for a ship expected to Bombay.

George ‘retired from service’ in 1783 when the Baroche was ceded to the Mahrattas. The Mahrattas were an indigenous warrior culture whose subcontinental empire had displaced the Moguls, then been displaced itself by Europeans. Negotiation with Mahratta leader, Sindia, who held several British hostages, culminated in the Company granting him Baroche in June 1782, though formal acceptance was delayed until March the next year.

George embarked on his final overland journey after August ’84. His final journey took him through ‘Persia, Arabia, Egypt, Asia Minor, Turkey, Greece, the Greek Islands…’ He also went to ‘Hungary, and almost all the countries and courts included in the usual continental tour. Attended only by an Arab suite, he performed a journey from Baghdad to Pera [likely Pera Magroon in north-west Iraq] …and traversing the wild regions of the Kurds…’

Gilbert Stuart, creator of Washington’s one-dollar bill portrait, painted George circa 1785. At last ready to realise his English country gentleman idyll, he headed to Bath, one of the best places to meet an eligible young lady. He met Catherine Nelson at a ball there in the winter of ‘86/87 and fell in love at first sight. They were married by his nineteen-year-old bride’s father, Reverend Edmund Nelson, at Walcot Church, Bath on 26th February 1787. She was the youngest sister of Horatio Nelson. Her not-yet-famous brother was a witness to their marriage settlement. This 18th century precursor to prenuptial agreements transferred the the groom’s estate to named executors as insurance for the bride and future children. George ‘assigned and transferred... one thousand six hundred and sixty six pounds thirteen shillings and four pence bank annuities unto the executors...’ namely Kitty’s father and brother, the Reverends Edmund and William Nelson, and her uncle, William Suckling.

Their first marital home, Barton Hall, was a grand red brick building on Barton Broad. According to their great-granddaughter, ‘At Barton... 'We walkt on the broad,” [Kitty] writes in May, “the water was calm and of a deep blue, corresponding to the etherial arch. How beautiful did the scenery round present itself…”’ It was here that the first children were born. George Nelson Matcham was born on 7th November 1789, and Henry Savage Matcham was baptised on 4th February 1791.

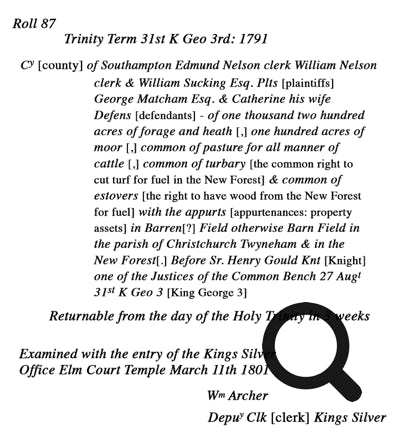

George and Kitty toured southern England in the summer of 1790 to seek land to manifest George’s country idyll. ‘They passed by Bath, Stonehenge and Salisbury with the object of seeing a property near Ringwood in Hampshire... what could please them better than building [a house] and planting the grounds with woods…” Building commenced in ‘91, and their new home, Shepherd’s Spring, was completed in ‘93. A 2017 New Forest magazine article states, ‘George Matcham... borrowed capital to do so, annually paying off the interest. His creditors were Nelson's father and brother, Edmund and William, and an uncle, William Suckling. The story appears to stem from an essay held by Ringwood Meeting House & History Centre, interpreting a 1791 legal document as a court order for George and his wife to promptly repay money to her father, brother and uncle. The writ’s date coincides with the start of building (see facsimile) so seems to be consent for land purchase.

George’s country gentleman idyll was completed by the employment of a gamekeeper, John Merryweather, at Plumley Heath, six-and-a-half-miles north of Shepherd’s Spring. Merryweather’s game duty is listed yearly in the Hampshire Chronicle from 1792 until 1796.

Many visitors ‘flocked to them undaunted by the abominable roads which led from Bath.’ But George realised his children’s education needs would be better met in Bath. He was reluctant to leave Shepherd’s Spring until, in the early months of 1798, his infant daughter, Mary Anne, died there at just a few months old.

They moved to No. 19 Kensington Place, Bath, ‘their home for many years.’ Their eighth-born, Harriet, was baptised in the newly extended parish church of Walcot St Swithin in September 1799. The city’s growing popularity as a spa and social hub had prompted a spate of grand, neoclassical redevelopment using gold-toned Bath rock.

George’s brother-in-law, Horatio Nelson, wrote to his wife, Fanny, in July 1797, ‘I never saw Sheppards Spring nor do I fancy if it was within our purse it would suit us.’ Although Fanny and her elderly father-in-law were frequent winter visitors to Bath, the Matchams hadn’t seen him for several years. Nelson finally joined them in Bath in September 1797 after the loss of his right-arm at Tenerife in July. ‘Sorrow was mixed with rejoicings… for he was in a miserable state of suffering’.

George and his father-in-law befriended the British Consul to the Balearics, Henry Stanyford Blanckley (known as H. S. B.). They had much in common. Both had been born abroad and spent most of their lives in warmer climates. Both had settled around English game-lands in the late 1780s (although H. S. B. had been employed as a gamekeeper, rather than employing one). And both were family-orientated men with many children.

In January ’98 when ‘A happy family party gathered at Bath, it’s pleasures enhanced by the Admiral’s presence in renewed health and spirits.’ Later that year, when news reached them of Nelson’s pivotal Nile victory, ‘there was much national and family rejoicing at the news.’ Nelson finally arrived home on 6th November 1800 with Sir William Hamilton and his wife, Emma. Nelson had been England’s superhero since his Nile victory, but Emma had already been famous as an ‘influencer’ who’d instigated the entire ‘Jane Austen’ fashion revolution. It became apparent that Britain’s two national treasures were amorously involved, despite being married to different people. The winter of 1800 saw Fanny subjected to a succession of public slights by Nelson in favour of Emma. He eventually walked out on her during a dinner and went to the Hamiltons, with whom he then permanently stayed.

On 3rd December 1800, George attended an elegant London dinner hosted by the East India Company for “the “Rt. Hon. Lord Nelson, for his service to his country.” George took advantage of the event to secure grants of Australian land for people he was helping to emigrate.

In 1801, at Nelson’s behest, Emma bought Merton Place in Surrey. Nelson felt guilty that it was partly financed by £4,000 loaned from George’s marriage settlement. ‘Mrs Matcham and her eight children’ as well as her siblings Susannah Bolton and Reverend William Nelson with their families spent Christmas there with Emma, but there’s no record of George’s attendance. Nelson biographer, Sugden, notes George ‘alone remained uncomfortable with the family’s treatment of Fanny’.

Now settled into city life without the distraction of land management, George applied himself to solving problems besetting the navy. On 29th January 1803, aided by his friend James Oliver, a patent was recorded for “GEORGE MATCHAM, of the city of Bath, Esquire ; for a principle or mechanical power for raising great weights, in preventing ships from sinking, in raising ships when slink, in rendering ships which are disproportioned to shallow-water capable of entering rivers, passing bars, or shoals, or otherwise moving in shallow water ; and for a variety of other useful purposes.”

A breakwater, completed in 1814, to protect to Plymouth’s naval harbour may have been ‘based on work when he was in India’, but George only learnt his design had been used when a friend urged him to claim recognition, but credit had already gone elsewhere. His great-granddaughter notes that his design to transform wetlands into ‘the pleasure grounds of St James’ Park was officially recognised’ (although sole credit seems have been given to James Nash).

George’s mother was buried at Bathford on 9th April 1803 (see photo above of Elizabeth Matcham’s domed tomb beside Nelson’s sister, Ann’s). She bequeathed most of her estate to George. He purchased a family residence at 2 Portland Place, Bath. An ‘elegant house [with] all necessary fixtures… substantially built, in a decent state of repair… and from the size of the principal rooms, well adapted for a large family.’

When Nelson departed for Trafalgar on 13th September 1805, the last person he spoke to was George Matcham. Nelson had publicly acknowledged paternity of his and Emma’s four-year-old daughter, Horatia (but continued to pretend she was Emma’s ward for fear of misogynistic backlash). ‘Nelson expressed regret that he had not yet been able to repay the £4,000 George had lent him.’ Horatia biographer, Gérin, suggests ‘it is not improbable that in these last moments’ Nelson asked George to protect Horatia if he died at Trafalgar.

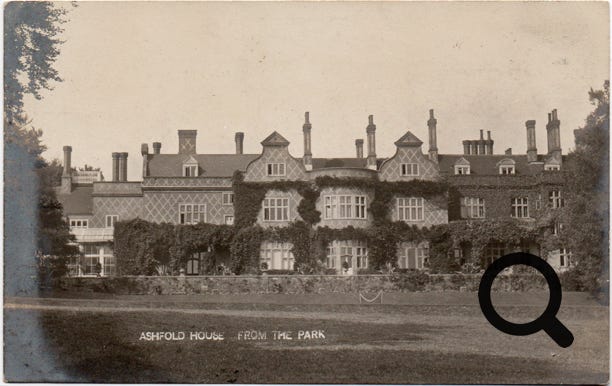

When news of Nelson’s death reached them in November, George and Kitty stayed in Merton to comfort Emma. Nelson’s siblings were gifted generous grants by the British government. William Nelson was given £120,000 and an earldom worth £5,000 a year; and Kitty and her sister Susannah were given £10,000, later increased to £15,000. George, re-embraced his country idyll by purchasing Ashfold Lodge, in Surrey, thirty-five miles due south of Merton.

By 1808, debt forced Emma to give up Merton. Nelson’s only dying wish – that Emma and Horatia received state pensions – had been systematically denied. Perhaps worse, the jointure of £800 a year he’d bequeathed her was administered by William Nelson who paid her nothing until 1808, and was then consistently tardy.

Biographer Kate Williams describes George as a man ‘of energy, but not much money... always looking for help with [his pack] of children’ who, after Nelson’s death, ‘inundated her with begging letters. Emma handed over more cash she did not have.’ Is there truth to this portrayal of George as a scrounger? The Matchams repeatedly aided Emma after Nelson’s death. For example, George lent her £100 in 1811, which she spent celebrating her 46th birthday.

Correspondence from George’s grandson, Major-General Montgomery Moore, is included in a reprint of Sichel’s 1891 Memoirs of Emma, Lady Hamilton, ‘Lady Hamilton was a frequent visitor at my grandfather's (Mr. Matcham) place, Ashfold Lodge, Sussex, for years after Lord Nelson's death, and my mother always spoke of her periodical visits to them as gala days, which the children of the family always looked forward to.’ On learning that Horatia had developed whooping cough in the winter of 1812/13, Kitty urged them to come to Ashfold. The Matchams were unaware Emma was confined to debtor’s jail. It was at this time that William Nelson ceased all payments of her jointure. George wrote to Emma in November:

‘We will supply you with potatoes all the winter, and send you a turkey by the first opportunity. If you find it impossible to pay us a visit, Mrs M. and I shall be tempted to go to Temple Place [the debtor’s prison] before the close of winter and pass a day with you.’

They invited her to tour Europe with them, but had no immediate plans to leave, and Emma was in a hurry to escape her debtors. Emma quietly sailed from London for Calais with Horatia on 2nd July 1814. When she died there on 15th January 1815, Horatia was stranded. Sichel’s account is refuted by another descendant, William Eyre Matcham. On page 313 of his copy of Sichel’s Memoirs, he underlined ‘Earl Nelson went to Calais’ writing ‘Not so’ in the margin, and, at the foot, ‘Mr. Matcham, not Earl Nelson, went over to Calais, and brought back Horatia to England dressed in boy’s clothes.’

According to Gérin, ‘At Ashfold Horatia found her five girl cousins (ranging in ages from twenty-three to eleven) and none of them as yet engaged, and the four boys whose education was mostly given at home. Tolerance, good-breeding and kindness were the family’s characteristics. The Matcham’s world, like the world of their contemporary Jane Austen, was conditioned by rural surroundings and limited society; its occupations and interests derived from the country pursuits and its pleasures were dependent on good neighbourliness... Their balls and parties were mostly impromptu affairs, organized between neighbours’.

George Matcham was keen to travel as soon as the Napoleonic wars ended. Gérin writes ‘Horatia's surviving correspondence tells us something about the family's trip abroad in 1816, which lasted from May to October. Lisbon was the objective, and there Mr. Matcham established connections with wine, fruit and vegetable exporters.’

They returned to England in early 1817 for the wedding of their eldest, George, to Harriet Eyre, heiress of the New House estate in Wiltshire. George and Kitty gifted them an estate adjoining Ashfold Lodge.” Returning to Europe, H. S. B. helped them find a house at Boulogne-sur-Seine, for the annual rent of £116, and a carriage into central Paris for £5 a week.

A succession of marriages for their daughters followed. The first was Harriet, who married H. S. B.’s son, Lieutenant Edward Blanckley R.N., on 24th April 1819, in Naples. For George and Kitty, now nearing seventy and sixty-five respectively, ‘Half settled in Paris, half spent in visits to England, a good many years passed away.’ Meeting again with Nelson’s spurned wife, they were ‘not sorry to renew old acquaintanceships.’

According to their great-granddaughter, ‘At last, Paris abandoned and Ashfold Lodge sold, a house in Holland Street, Kensington, became their final home. From thence, long yearly visits were paid to George (Jr.) and his wife, each equally devoted to the old couple. By the grandchildren they were adored... Full as ever of his hobbies, G. M. would potter about on his long-tailed pony, with a stream of little grandchildren running or riding after him, to whom he was a perpetual delight and playfellow.... He would have his own workmen; and carry on improvements to his heart's desire. A large pond was dug one year. Planting and cottage building absorbed him. Stories of him and his factotum; one Noyce, still linger in the family.’

George Matcham died, aged seventy-nine, in his and Kitty’s house at Holland Park in Kensington.

References

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co., pp. 30–31.

Forbes, J., 1834. Oriental Memoirs. [online] Google Books. Available at: <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=r2IOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA420&lpg=PA420&dq=matcham+bombay+mermaids&source=bl&ots=cBDdp7OsH2&sig=V3mPtkeUwKFFYbHQdHja-RgjNos&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjL8uG0zojPAhWpD8AKHY73CIoQ6AEINjAF#v=onepage&q=matcham%20bombay%20mermaids&f=false> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co., pp. 30–31.

Markley, Robert. “‘A PUTRIDNESS IN THE AIR’: Monsoons and Mortality in Seventeenth-Century Bombay.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, vol. 10, no. 2, [Indiana University Press, University of Pennsylvania Press], 2010, pp. 105–25, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23242143.

Charterhouse archivist correspondence with author by email, 2016.

Search.findmypast.co.uk. 2022. George Matcham in 1770, British India Office Births & Baptisms. [online] Available at: <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=BL%2FBIND%2FJ-1-8-PART1%2F00103&parentid=BL%2FBIND%2F393> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

Ancestry.com. UK, Registers of Employees of the East India Company and the India Office, 1746-1939 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2018.

Wiki.fibis.org. 2022. Senior Merchant - FIBIwiki. [online] Available at: <https://wiki.fibis.org/w/Senior_Merchant> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

En.wikipedia.org. 2022. East India Company - Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_India_Company> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Battle of Plassey - Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Plassey#Battle> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

the Guardian. 2022. The East India Company: The original corporate raiders | William Dalrymple. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company-original-corporate-raiders> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

Covey-Crump, P., 2022. Glimpses from the life of an 18th century English merchant who made a fortune selling salt in Bengal. [online] Scroll.in. Available at: <https://scroll.in/magazine/855386/glimpses-from-the-life-of-an-18th-century-english-merchant-who-made-a-fortune-selling-salt-in-bengal> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

Families in British India. 2022. 1765 List of the Honble Company's Marine Officers, Free Merchants & Seafaring Men in private employ in Bombay and Factories Subordinate. [online] Available at: <https://fibis.ourarchives.online/bin/aps_detail.php?id=1122935> [Accessed 12 February 2022].

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900/Matcham, George.” [n.d.]. Wikisource.Org <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Matcham,_George> [accessed 12 February 2022]

Google Books.” [n.d.]. Google.Co.Uk <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Cambridge_Economic_History_of_India/9ew8AAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=broach+gujarat&pg=PA347&printsec=frontcover> [accessed 12 February 2022]

Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe P 32

Outlet. 1990. Bombay Marines (Random House Value Publishing) [accessed 12 February 2022]

Emin, E. J., J. Emïn, and A. Apcar. 1792. Life and Adventures of Emin Joseph Emin, 1726-1809 (Baptist mission Press) pp. 474–475

British India Office Ecclesiastical Returns - Deaths & Burials. Copyright brightsolid online publishing ltd. < https://www.findmypast.co.uk/transcript?id=BL/BIND/D/368260> [accessed 13 February 2022]

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co., p. 32.

"Passage East.” [n.d.]. <http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/m/marshall-east.html> [accessed 12 February 2022]

[N.d.]. Jstor.Org <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1779587?read-now=1&seq=7#page_scan_tab_contents> [accessed 12 February 2022]

Wikipedia contributors. 2022. “Eyles Irwin,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eyles_Irwin&oldid=1068036765>

Jstor.Org <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1779587?read-now=1&seq=7#page_scan_tab_contents> [accessed 12 February 2022]

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co., pp. 32–33

[N.d.-b]. Jstor.Org <https://www.jstor.org/stable/44143063?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents> [accessed 13 February 2022]

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co., pp. 33–34

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co., p. 31

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co., p. 34

Ibid.

Google Books”———. [n.d.-b]. Google.Co.Uk <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Series_of_Adventures_in_the_Course_of/_VVWAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0> [accessed 13 February 2022] p. 283

Google Books”———. [n.d.-c]. Google.Co.Uk <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Series_of_Adventures_in_the_Course_of/_VVWAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=eyles+irwin+voyage+up+the+red+sea&printsec=frontcover> [accessed 13 February 2022] p. 290

Google Books”———. [n.d.-c]. Google.Co.Uk <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Series_of_Adventures_in_the_Course_of/_VVWAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=eyles+irwin+voyage+up+the+red+sea&printsec=frontcover> [accessed 13 February 2022] p. 293

Google Books”———. [n.d.-c]. Google.Co.Uk <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Series_of_Adventures_in_the_Course_of/_VVWAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=eyles+irwin+voyage+up+the+red+sea&printsec=frontcover> [accessed 13 February 2022] p. 315

Tigris.” [n.d.]. Mcgill.Ca <https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/t/Tigris.htm> [accessed 13 February 2022]

Google Books”———. [n.d.-c]. Google.Co.Uk <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Series_of_Adventures_in_the_Course_of/_VVWAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=eyles+irwin+voyage+up+the+red+sea&printsec=frontcover> [accessed 13 February 2022]. P 331

Google Books”———. [n.d.-c]. Google.Co.Uk <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Series_of_Adventures_in_the_Course_of/_VVWAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=eyles+irwin+voyage+up+the+red+sea&printsec=frontcover> [accessed 13 February 2022] p. 381

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900/Matcham, George.” [n.d.]. Wikisource.Org <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Matcham,_George> [accessed 12 February 2022]

“Maratha Empire,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Maratha_Empire&oldid=1071191267>

Thomas, R. H. 1851. Treaties, Agreements, and Engagements, between the Honorable East India Company and the Native Princes, Chiefs, and States, in Western India, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, &c: Also between Her Britannic Majesty’s Government, and Persia, Portugal, and Turkey (government at the Bombay Education Society’s Press) Pp. 707-708

Emin, E. J., J. Emïn, and A. Apcar. 1792. Life and Adventures of Emin Joseph Emin, 1726-1809 (Baptist mission Press). Pp 476

“Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900/Matcham, George.” [n.d.]. Wikisource.Org <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Matcham,_George> [accessed 12 February 2022]

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co. Pp. 35–37

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co. P. 36

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 1 Mar 1787

“Settlements and Entails.” [n.d.]. Nottingham.Ac.Uk <https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/deedsindepth/settlements/settlements.aspx> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Wikipedia contributors. 2020. “Marriage Settlement (England),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Marriage_settlement_(England)&oldid=976746082>

Wiltshire and Swindon Archive photo taken by David Bullock on 02/04/2016

Wikipedia contributors. 2021. “Barton Broad,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Barton_Broad&oldid=1008576984>

Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe P. 59

Ancestry.com. Norfolk, England, Church of England Baptism, Marriages, and Burials, 1535-1812 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016. <https://www.ancestry.co.uk/imageviewer/collections/61045/images/4098101_00021?ssrc=pt&treeid=82673375&personid=40467016594&hintid=&usePUB=true&usePUBJs=true&pId=1121158>

https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryui-content/view/84398946:9841?ssrc=pt&tid=82673375&pid=40467016984

Martin, John. [n.d.]. “A History of Landford in Wiltshire Part 10 -Newhouse,” Wordpress.Com <https://landfordhistory.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/A-History-of-Landford-Part-10-Newhouse.pdf> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Ibid.

“The St Leonards & St Ives Directory - October 2017.” 2017. Issuu <https://issuu.com/dorsetpublications/docs/slsid_october_2017_-_web> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Matchams folder held by Ringwood Meeting House & History Centre. Accessed October 2015.

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co P. 92

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co P. 135

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co P. 145

Matcham, M., 1911. The Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe. 1st ed. New York: John Lane Co P. 148

Martin, John. [n.d.]. “A History of Landford in Wiltshire Part 10 -Newhouse,” Wordpress.Com <https://landfordhistory.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/A-History-of-Landford-Part-10-Newhouse.pdf> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Peakman Julie, Emma Hamilton. Haus Publishing, London (2005). P 110.

Martin, John. [n.d.]. “A History of Landford in Wiltshire Part 10 -Newhouse,” Wordpress.Com <https://landfordhistory.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/A-History-of-Landford-Part-10-Newhouse.pdf> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Hampshire Chronicle 08 December 1800. [n.d.]. Findmypast.Co.Uk <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/bna/viewarticle?id=bl%2f0000230%2f18001208%2f004&stringtohighlight=nelson%20east%20india> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Martin, John. [n.d.]. “A History of Landford in Wiltshire Part 10 -Newhouse,” Wordpress.Com <https://landfordhistory.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/A-History-of-Landford-Part-10-Newhouse.pdf> [accessed 16 February 2022]

“Here Was Paradise - A Description of Merton Place, by Peter Warwick.” [n.d.]. Wandle.Org <http://www.wandle.org/aboutus/nelson2005/footnotes.htm> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Peakman J., Emma Hamilton. Haus Publishing, London (2005). P 127

Sugden, J., Nelson: The Sword of Albion, Volume 2 (2012). Random House. P. 760

https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Repertory_of_Patent_Inventions/O9Y0AAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=george+matcham+patent&pg=PA320&printsec=frontcover

https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Repertory_of_Patent_Inventions/O9Y0AAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=george+matcham+patent&pg=PA320&printsec=frontcover

“Plymouth Breakwater,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plymouth_Breakwater&oldid=1056839491>

Martin, John. [n.d.]. “A History of Landford in Wiltshire Part 10 -Newhouse,” Wordpress.Com <https://landfordhistory.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/A-History-of-Landford-Part-10-Newhouse.pdf> [accessed 16 February 2022]

"St James’s Park,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=St_James%27s_Park&oldid=1070165712>

Ancestry.Co.Uk <https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryui-content/view/52597:5111?ssrc=pt&tid=82673375&pid=40467016521> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Wiltshire and Swindon Archive record viewed 02/04/2016

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 31 December 1807. Findmypast.Co.Uk <https://search.findmypast.co.uk/bna/viewarticle?id=bl%2f0000221%2f18071231%2f021&stringtohighlight=matcham> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Robinson S. K., In defence of Emma (2015) P. 352.

Gérin W., Horatia Nelson Oxford University Press (1970). P. 100

Robinson S. K., In defence of Emma (2015) P. 379.

Peakman J., Emma Hamilton. Haus Publishing, London (2005). P 145.

Fraser F., Beloved Emma. Weidenfield and Nicholson. London (1986). P. 342

Warwick, Peter. [n.d.]. “Here Was Paradise,” Wandle.Org <http://www.wandle.org/aboutus/nelson2005/paradise.htm> [accessed 16 February 2022]

Peakman J., Emma Hamilton. Haus Publishing, London (2005). P 147

Robinson S. K., In defence of Emma (2015) P. 438.

Williams K., England’s Mistress, Random House (2006). P. 281.

Williams K., England’s Mistress, Random House (2006). P. 329.

Peakman J., Emma Hamilton. Haus Publishing, London (2005). P 153

Walter Sichel 'Memoirs of Emma, Lady Hamilton', W. W. Gibbings (1882) p.294. Digitised 16 June 2010 <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Memoirs_of_Emma_Lady_Hamilton/-9wxAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0>

P. 184

Ibid

Robinson S. K., In defence of Emma (2015) P. 438.

Robinson S. K., In defence of Emma (2015) P. 446.

Peakman J., Emma Hamilton. Haus Publishing, London (2005). Pp. 156-7

Robinson S. K., In defence of Emma (2015) P. 449.

Book shown to author in October 2017.

Gérin W., Horatia Nelson Oxford University Press (1970). P. 219.

Gérin, W. (1970). Horatia Nelson. Oxford: Clarendon P. 218

Gérin, W. (1970). Horatia Nelson. Oxford: Clarendon P. P. 222.

Gérin, W. (1970). Horatia Nelson. Oxford: Clarendon P. P. 231.

Gérin, W. (1970). Horatia Nelson. Oxford: Clarendon P. P. 224.

Gérin, W. (1970). Horatia Nelson. Oxford: Clarendon P. P. 232.

Gérin, W. (1970). Horatia Nelson. Oxford: Clarendon P. P. 234.

Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe P. 293.

Nelsons of Burnham Thorpe P. 295.

Dictionary of National Biography, Volumes 1-22 for George Matcham.