Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact | Facebook

The Rise of the Fouled Anchor

The visual codification of the Royal Navy during the 1700s

(First published in the Trafalgar Chronicle in 2020)

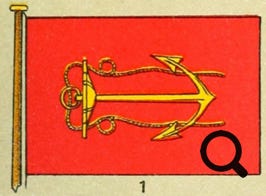

The Royal Navy at the start of the Georgian period in 1714 looked nothing like it’s glamorous Nelson-era counterpart at the century’s end. Lacking designated uniforms, officers were viewed as ‘base, coarse and unrefined’. However, less than a century later, Royal Navy officers were resplendent in blue and white uniforms emblazoned with gilt buttons sporting the fouled (rope-strewn) anchor motif, which is still in use today. What caused the Navy to change from ill-reputed mufti to uniformed respectability, and from whence, out of the blue, did the iconic fouled anchor arise?

Naval use of the anchor motif, albeit un-fouled, can be traced back to the Lord Admirals of Scotland in 1515. The first record of its use by the English Admiralty comes forty-three years later in the reign of Queen Mary. The fouled version first appears in the seal of the Earl of Nottingham, Lord High Admiral, in 1601. In 1619, Nottingham’s successor Buckingham, was granted “an Ensigne with ye Ld Admiralls Badge & Motto”. This appears to have been the fouled anchor because he adopted it as his emblem. The fouled anchor, according to the Oxford Companion to ships & the sea, is ‘an abomination to seamen when it occurs in practice, as the seal of the highest office of maritime administration is purely on the grounds of its decorative effect, the rope cable around the shank of the anchor giving a pleasing finish to the stark design of an anchor on its own.

The first English language naval dictionary, entitled A Naval Expositor, was produced circa 1732 by Thomas Blanckley, Clerk of the Survey for Portsmouth Dock. His dictionary ‘SHEWING all the Words and Terms of Art belonging to the Parts, Qualities, Proportions of Building, Rigging, Furnishing and Fitting a Ship for Sea’ includes meticulously hand-drawn illustrations, the first of which is of an anchor. Blanckley’s definitions gift the modern reader with a fascinating window onto the inner workings of the early Georgian navy, and bear trace of his intellectual struggle to codify naval hardware into concise, accurate phrases. His definition of ‘board’ is three-plied:

Elm: Is used for several Services about the Yard, on board ships, & repairing Boats &c

Firr: For sheathing ships bottoms, flooring their cabbins, & masking moulds &c

Wainscot: For building Barges, Pinnaces, & Wherrys & other uses relating to the Joyner.

A humiliating Royal Navy defeat to the French and Spanish at Toulon in 1744 was offset by the heroic return of Commodore George Anson. He, and the one-hundred-and-eighty-eight men who returned with him, had survived marooning in the Pacific to capture a Spanish Manila galleon carrying a fortune in cargo. Anson earned £91,000 prize money from the haul, and pathway into the Board of Admiralty. One of the Board’s senior officers, Edward Vernon, was actively determined to reform the sluggish, ineffective navy. Anson, equally keen, combined forces to implement his reforms. Of these, one, instigated in 1748, was the ruling that all commissioned officers must wear uniform. This served to unite officers as a proud brotherhood clearly distinguished from the coarse hoi polloi of uncommissioned crew. Confusingly, however, no pattern was at first decreed. The introduction of naval uniform mirrored the impact of Thomas Blanckley’s illustrated dictionary as a revolutionary step in visually codifying the navy.

Anson biographer Sir John Barrow wrote in 1839 that blue and white was chosen for the Royal Navy’s uniform on the whim of George II, who had been impressed by the appearance of the Duke of Bedford’s wife riding in those colours. However, the author concedes, the story may be nothing more than colourful rumour.

Thomas Blanckley died in Portsmouth on the morning of 29th December 1747 aged sixty-nine. His eldest son, Thomas Riley, who had already taken his position of Clerk of the Survey, inherited his Naval Expositor manuscript. Quick off the mark, he commissioned the esteemed London-based Huguenot printmaker, Paul Fourdriniers, to produce copperplate engravings of his father’s illustrations, and recruited subscribers to finance mass printing. He was evidently supported by Anson, as the subscribers list is headed by “RIGHT Honourable the Lords of the Admiralty (as a board)”. Also named is the Duke of Bedford (whose wife’s attire was rumoured to have inspired the navy uniform’s colours) and Joseph Allin: Surveyor of His Majesty’s Navy and his father-in-law. The printed version of the Naval Expositor, released in 1750 comprises an elaborate frontispiece surmounted by a fouled anchor. This appears to be the first instance of the motif being used to represent the navy, rather than the Admiralty only. Beneath the fouled anchor, the words ‘by Thomas Riley Blanckley’ are prominently emblazoned. It is unclear, however, whether he deliberately set out to fool posterity into believing he created the Naval Expositor, because he acknowledges the true authorship in his will (proved 23rd May 1753):

“Also I give and bequeath all the manuscripts of my late ffather… Also I give and bequeath the copper plates and blank books of the Naval Expositor composed by my late ffather and lately by me published…”

In the latter part of the decade, in 1758 (the birth year of Horatio Nelson), buttons bearing the fouled anchor were produced for Royal Navy officers’ uniforms. This, however, pre-dated their formal introduction by sixteen years. The fouled anchor was now, for the first time, associated with Royal Navy officers.

News in 1772 – the year after Horatio Nelson joined the navy – that the fouled anchor was being formally added to Royal Navy buttons was lamented as a downslide into the capricious following of fashion; and that the anchor motif was fit only for servants, not the great heroes of the British navy. The anchor, it was argued, had since Old Testament times symbolised hope, and should not therefore be purloined. If given choice over the design of their personal buttons, as huntsmen had, officers could signal their personal disposition, knowledge and taste by choosing ‘a Variety of marginal engravings, full as entertaining and as useful as those which illustrate Blankley’s Naval Expositor’. Nonetheless, anchor buttons were introduced two years later. The Hampshire Chronicle reported on 13th June 1774:

“We are informed that the Captains uniform of the navy is going to be altered, and that Sir Richard Bickerton will appear in the new dresses at the sea-ports when Lord Sandwich is there, for the approbation of the corps, the old coat is to have the addition of a row of lace round the pockets and sleeves, with anchor buttons ; and the undress frock is to be lapelled with blue, with button-hole, worked with gold thread, anchor buttons, plain white waistcoat and breeches. After the approbation of the corps is obtained, it will be shewn to his Majesty for his concurrence.”

This ongoing visual codification process enabled people to picture the navy in their minds’ eyes. Like modern day football clubs, the Royal Navy now had its own colours and an emblem (the fouled anchor). Thus branded, a pictorial snowballing effect took place as artists and cartoonists translated all things naval into mass-produced prints, graphically emblazoning the Royal Navy in public consciousness. The momentum of this visual snowballing effect was so great; its glamour so strong that Louis XVI of France wished to mimic it and decreed the use of blue and white and anchor buttons for his navy. An unspecified English gentleman in Paris wrote in the summer of 1786:

“…I was highly pleased to see, in consequence of the new Order from the King for regulating the Marine uniform, that it is entirely formed upon that worn by the British naval Commanders. Even the Anchor upon the Button has been introduced in preference for the Fleur de Lys. In short, English Fashions now prevail here as much as French did with us formerly.”

Louis XVI’s anglicisation of the French navy was quickly curtailed by the French revolution, which began in May 1789. No longer aspiring to mimic, the French now sought to impose their new republican government on Britain. So began the revolutionary wars, from which the aspiring young naval captain Horatio Nelson stepped forwards into glory. Having cut his teeth defeating Napoleon’s forces at Capo Noli in 1795, his resounding victory at the Nile on 1st August 1798 cast him as the superhero protector of all who resisted the encroaching republican yoke. Women in England wore ‘gold anchors that celebrated their hero’. In Naples Emma, Lady Hamilton, who was at this time the fashion-setter of Europe, and bosom friend of Queen Maria Carolina, the sister of the ill-fated Marie Antoinette, wrote to him adoringly on September 3rd:

“My dress from head to foot is alla Nelson ... Even my shawl is in blue with gold anchors all over. My earrings are Nelson’s anchors; in short, we are be-Nelsoned all over.”

The fouled anchor, whose naval use had risen rapidly during the latter half of the eighteenth century, had transmogrified to symbolise not just the Royal Navy, but a new, international hero: Horatio Nelson, who, in dashing navy blue and white festooned with gold fouled anchors and medals of valour, epitomised the rebranded navy. Exultant and adoring, the Hamiltons commissioned a lavish dinner service as a gift for his fortieth birthday on 29th September 1798, with enormous fouled anchors pride of place on every dish.

References

Historic Dockyard Chatham, ‘the fouled anchor button’, online article (accessed January 2020) https://collection.thedockyard.co.uk/objects/9028

Perrin W. G., ‘British flags, their early history, and their development at sea; with an account of the origin of the flag as a national device’, Cambridge University Press (1922). P. 82

Kemp. P., “Oxford Companion to ships & the sea” Oxford University Press (1976) quoted in Lindfield P., and Margrave C., “Rule Britannia?: Britain and Britishness 1707-1901” Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2015). P. 58

Wilson B., “Empire of the Deep: The Rise and Fall of the British Navy” Hatchette UK (2013) Chapter 27 and 28

Barrow. J., ‘The Life of George, Lord Anson, Admiral of the Fleet, Vice-admiral of Great Britain, and First Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty, Previous To, and During, the Seven Years' War’, J. Murray (1839). P. 150

Ibid.

Historic Dockyard Chatham, ‘the fouled anchor button’, online article (accessed January 2020) https://collection.thedockyard.co.uk/objects/9028

Public Advertiser 27 May 1772

Hampshire Chronicle 13 June 1774. P. 3

Wilson B., ‘Empire of the Deep: The Rise and Fall of the British Navy’, Orion Publishing Group

(2013). Introduction to ch. 28

Derby Mercury 01 June 1786

Williams K., ‘England’s Mistress’, Hutchinson (2006). P. 205.

Robinson S. K., ‘In Defense of Emma. Scheming Adventuress or Radiant Presence?’, CPI Books UK (2016). P. 167.

BADA Ltd. Website. Viewed January 2020 https://www.bada.org/object/admiral-lord-nelsons-birthday-service-1798