Lily Style Author

CATHERINE ANN HARMER: AN EARLY 19TH CENTURY FARMER’S WIFE

Originally published to Harmer Family Association newsletter 2021

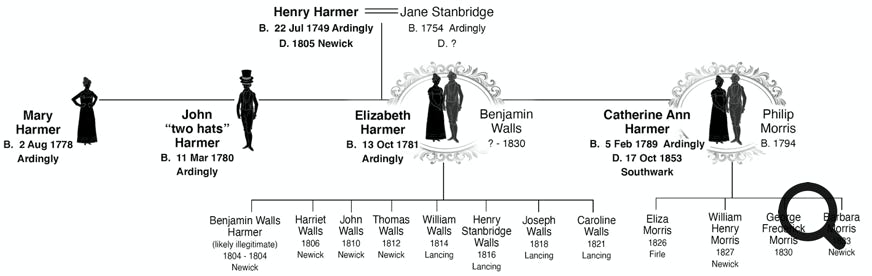

It’s easy when researching ancestors to slip into focusing only on the lives of our male forebears. After all, it’s they who invariably took jobs, kept their family surname and otherwise made it into records. We are though, all of us, equally descended from female forebears. Their lives tend to neither be well-recorded, nor thought of. This article seeks, in a very small way, to redress the balance by exploring the life of my 3rd great-grandmother, Catherine Ann Harmer, who was born in the west Sussex village of Ardingly in 1789, and married a farmer, Philip Morris, in 1823. What was her life experience as an early 19th century Sussex farmer’s wife?

Nicola Verdon, in an essay posted on British Agricultural History Society’s website, colourfully conjures cultural perceptions of English farmer’s’ wives in this era:

Was the farmer’s wife the frivolous character caustically condemned in the 1820s by William Cobbett as the ‘Mistress within’, delighting in the showy decorations of her newly refurbished parlour and overseeing the education of her children into ‘young ladies and gentlemen’? Or was she a business partner, directing certain departments of the farm economy with ‘so large a portion of skill, of frugality, cleanliness, industry, and good management ... that without them the farmer may be materially injured’, as one of Cobbett’s contemporaries [J. C. Loudon] proposed? https://www.bahs.org.uk/AGHR/ARTICLES/51n1a2.pdf

Verdon expands that the reality was that farmer's wives of this period were “a remarkably diverse group in rural society” spanning “the whole spectrum from the tirelessly hard-working companion to the genteel, leisured spouse”.

Which category did Catherine Ann Harmer fit, or did she lie somewhere in between the two poles of farm wife’s potential, being neither tirelessly hardworking, nor idly genteel and leisured? Records tell that she spent her married life living in Brett’s Farm, Newick, which her husband co-ran with her brother, John.

Her brother John Harmer always wore at least two hats, and was the subject of an article I submitted to the March 2021 HFA newsletter. I have since realised that John “two hats” and Catherine Ann’s sister, Mary, had not, as was supposed, died in 1811 as Mrs William Bugden of West Hoathly, but remained living as a spinster in Cliffe, Lewes. Similarly, contrary to my article in the March 2021 HFA newsletter, it was Mary Harmer, not Catherine Ann, whose rent for a house in Cliffe was paid for when “two hats” tried, repeatedly, to assert voting rights for Cliffe on the grounds that he paid for the rent of his sister’s house there. Mary Harmer’s tenancy of the Lewes house is attested both in the 1841 census, and in her probate record.

So what exactly was the life of an early 19th century farmer’s wife? According to Bridget Hill (1994), in the mid eighteenth century, a trend began in the south and east of England for farmer’s wives to seek refinement by distancing themselves from involvement with manual labour. When Catherine Ann married Philip Morris in 1823, the fashion in south-east England was for farmer’s wives to behave as refined, clean-handed gentleladies would have been long-engrained. According to hisour.com, regency style fashion (1810–1820) was:

"based on the Empire silhouette — dresses were closely fitted to the torso just under the bust, falling loosely below. Regency fashion was quite different from the styles prevalent during most of the 18th century and the rest of the 19th century, when women’s clothes were generally tight against the torso from the natural waist upwards, and heavily full-skirted below (often inflated by means of hoop skirts, crinolines, panniers, bustles, etc.). The high waistline of regency styles took attention away from the natural waist, so that there was then no point to the tight “wasp-waist” corseting

often considered fashionable during other periods. Without the corset, chemise dresses displayed the long line of the body, as well as the curves of the female torso.”

We can gain a glimpse of Catherine Ann’s style in a miniature portrait of her mother-in-law, Susannah Morris née Medhurst (1758–1837). Widowed in 1801, she remained living in the Morris family farm at Ranscombe, Firle, Sussex, which was managed by her eldest-living son, Thomas, until her death in 1837. Her portrait depicts her with the short-cropped hair that was fashionable in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Her white blouse has a high, tight-gathered collar which is similar to an 1815 illustration of French morning dress.

Catherine Ann’s husband, Philip Morris, was the youngest son of a farmer named Anthony Morris (1738–1801) and Susannah Medhurst (1758–1837). The Morrises lived 10 miles south of Newick at Ranscombe Farm, Firle, near South Malling on land leased from Henry Viscount Gage. The Gage family, who had lived in Firle House since Tudor times, is perhaps most notable for giving their name to the plum-relative, greengages. The story goes that the fruit was first imported to England in 1724 bySir William Gage, 7th Baronet, of Firle. According to Firle House’s website, the Gages had been:

“staunch Catholics until the eighteenth century and for nearly 150 years life was difficult for the recusant Gages. The Acts of Settlement of 1701 helped to bring an end to the religious persecutions and fanatical feelings of the seventeenth century, coupled with the decision of Sir William Gage, 7th Bart (1695-1744), to conform to the Church of England brought a very different atmosphere to Firle. The family took part in public life and service again and were created Viscounts.”

Interestingly, my late granduncle, Frank Langford – an enthusiastic amateur genealogist, grandson of Catherine Ann Harmer, and former member of HFA – wrote to his brother, Eric, in 1982:

“I’m having less luck with the Morris line, probably because they were Catholics. It wasn’t because of religious prejudice, apparently, but because the Catholic records were kept separately by them, burials were often (but not always) in separately consecrated ground, and so on. It seems clear however that ‘our’ Morrises belonged to that part of this county [Sussex] consisting of the parishes of South Malling and Ranscombe…”

In another letter, Frank Langford elaborates of Philip Morris:

“He is said to have been a steward on one of Viscount Gage’s estates in Ireland at one time, and to have lived at Gibraltar Farm near Lewes. This is certainly on Gage’s land but I cannot trace any confirmation of this story…”

So it seems both the Morrises and the aristocratic Gages of Firle had Catholic roots. The Morrises’ precise relationship with the Gages is hard to pinpoint, as scant conclusive documentation remains. There are, however, a number of pointers which may, or may not, directly relate to the Gages of Firle and the Morris family that Catherine Ann married into in 1823. For example, there’s a note on Firle House’s website that between 1713 and ’44 work on the house was carried out by the masons Arthur and John Morris of Lewes, who operated a virtual monopoly in the area. Heading now to New York, A Naval Biographical Dictionary entry tells us that a boy was baptised Henry Gage Morris in 1770, who was the only surviving son “of the late Hon. Lieutenant-Colonel Roger Morris, a member of the Governor’s Council at New York, who served with distinction in the first American war.” The intriguingly named Henry Gage Morris took a naval career, and was made Rear-Admiral of the British navy in 1846.

As we’ve seen, the family story passed down to Frank Langford is that Catherine Ann’s husband-to-be, Philip Morris, was employed as a steward on a Gage estate in Ireland in the late 18th or early 19th century. Newspaper clippings show that the Gages and Morrises maintained contact during the early 1800s, with leases being renewed for the Morrises to remain on Gage land at Firle.

Catherine Ann’s wedding to Philip Morris took place in St Peters, West Firle, on 20th January 1823. Philip was of the parish, and she of Cliffe, Lewes. The witnesses were a man named John Hillman, and Catherine Ann’s unmarried sister, Mary Harmer. It seems probable the sisters had been living together in Cliffe prior to the wedding. Further, a merchant named Thomas Hillman was a neighbour of Mary Harmer’s Cliffe house when the 1841 census was taken, so it seems likely that the other marriage witness, John Hillman, was their neighbour.

Their marriage having taken place three years after the end Regency era, a Jane Austen Centre blogpost about Regency weddings can be thought descriptive:

“most weddings in Jane Austen's time were private, family affairs. Even fashionable weddings at the church of choice of the day were but sparingly attended, usually only by close relatives or, if in the village church, by the local inhabitants. The bride did have a few attendants, mainly unmarried younger sisters or cousins. The groom commonly had his best man and the witnesses, of course. Usually the bride's parents attended, as well. What about the lavish party? Well, there wasn't always one! Consider Charlotte Lucas' wedding day in Pride and Prejudice, "The wedding took place; the bride and bridegroom set off for Kent from the church door."

“...How common the white wedding dress was during the Regency era is hard to say, but we have some reasons to suspect that it was more prevalent than many may think. Although no bridal fashion prints survive from before 1813, paintings of wedding scenes, such as Highmore's 1743 illustration for Samuel Richardson's Pamela, do depict brides in white. Veils seems to have become popular somewhat later in the century so most brides either wore flowers in their hair, a cap or sometimes a hat. When Jane Austen's niece Anna married Benjamin Lefroy in 1814, she wore "a dress of fine white muslin, and over it a soft silk shawl, white shot with primrose, with embossed white-satin flowers, and very handsome fringe, and on her head a small cap to match, trimmed with lace." Although bouquets and flowers with personal meanings came into vogue during the Victorian era, flowers and herbs have been used in weddings since the beginning of time as a way of

showing love and well wishes to everyone.”

Now married, did Catherine Ann conform to William Cobbett's stereotype of 1820s farmer’s wives by “delighting in the showy decorations of her newly refurbished parlour and overseeing the education of her children into ‘young ladies and gentlemen’?” Verdon (in her essay cited above) goes on to argue that 19th century farmer’s wives, even if superficially genteel, carried out much hands on farm-management:

“On the surface Elizabeth Cotton, who lived with her husband and six children on their 400-acre farm in Suffolk in the 1850s and 1860s, would seem a typical representation of the refined farmer’s wife. She oversaw the renovation of the farmhouse, employed a dairymaid and housekeeper and engaged fully in the social activities of near-by Ipswich. Yet she still attended to business callers, opened her kitchen to labourers, was expected to take charge of the farm in her husband’s absence, supervised the dairy and had to deal with the transgressions of her light-fingered maid.

Farmers’ wives continued to take responsibility for the dairy, poultry, pigs, garden and kitchen, either performing the work herself or superintending the labour of others. Although her labour generated profit, the farmer’s wife was not formally paid for her work. As a result it is largely hidden in the sources.”

It therefore seems likely that Catherine Ann would have been conflicted between the fashion of deporting herself as an idle gentlelady with a cordial family connection to the Gages, and an inescapable everyday burden of manual duties.

The Jane Austen Centre website describes the agricultural world Catherine Ann inhabited, “at the dawn of the nineteenth century ... fully one-third of the population of England was employed in agriculture. Like farmers in all times and places, the rural folk of Jane’s English countryside were at the mercy of the weather ... crops and livestock could be devastated by too much cold or not enough rain. Poor weather also encouraged the spread of blights and rots. When the wheat harvest was bad, the price of bread shot up, making it hard for the poor to feed themselves, and riots over food would sometimes erupt among the rural hungry.” However:

“country living was not without its charms and pleasures. The boring toil of agricultural work was broken by seasonal festivals such as May Day. Towns had markets which provided a venue in which country people could sell their food, including such edibles as poultry, eggs, and vegetables. If these markets outgrew their original surroundings, then fairs were held outside the towns in nearby fields. The fairs became ever larger when merchants selling tools, cheese, clothing, earthenware, and leather goods arrived. With so many people present, other vendors began to sell food and drink to the visitors. Sports and other games were also part of the festivities, with the fair becoming something far greater than its original purpose of being a place to sell farm produce. Dancing was also included in a fair’s usual list of activities, and was a popular form of entertainment everywhere. For a young middle-class woman such as Jane, residing in the country, dancing was a premier delight. It was on the dance floor where she could meet people and make friends. The countryside was not disconnected from the wider world.”

Both Newick and Firle held regular fares in which prizes were awarded for livestock and crops. When her brother “two hats” John Harmer won a prize for currants at Newick Horticultural Society’s autumnal meeting in September 1833, a Sussex Advertiser reporter noted, “we do not remember any former meeting to witness so numerous an attendance of fashionable company.”

Successive newspaper reports during the early decades of the 19th century tell that Catherine Ann’s brother-in-law, Thomas, remained living on the Morrises’ home farmstead at Ranscombe as a sheep farmer frequently called to judge local agricultural competitions. One of these, in June 1837, was on Lord Gage’s estate. Expertise aside, the Sussex Advertiser reported on 13th February 1826 that “One prime lot of three year old Wethers, belonging to Mr. Morris, of Ranscomb, fetched full 5s. 9d. per stone; and even at that high price it seems, produced no profit for the grower, who had fatted them with acorns and beans.” Catherine Ann’s mother-in-law, Susannah, had remained living at Ranscombe Farm throughout this lean period, as told by her obituary in the Sussex Advertiser on 17th April 1837:

“Died

On the 15th instant, at Ranscombe, near Lewes, Mrs Susannah Morris, aged 79, relict of the late Anthony Morris.”

Catherine Ann, as farmer’s wife to Philip Morris, had been living in Newick at Brett’s Farm, which was co-managed by her indomitable brother, John “two hats” Harmer. Still standing in the present day, the farm comprises neat, red brick buildings fronting Newick village green. The 1841 census records Philip Morris, Farmer, and his wife Catherine living on Newick Green with various servants, and John Harmer ("two hats”). There is no mention, however, of any of Catherine Ann and Philip Morris’s children (we’ll come back to them).

Brett’s Farm didn’t specialise in sheep as the Morrises at Ranscombe did. An 1860 auction notice describes the farm as “compact with house, barn, stable lodges and yards and productive arable, pasture, meadow and hop land in a state of high cultivation."

According to a 2009 Cambridge University paper, by Lucy Walker, the cultivation of hops in Sussex “was concentrated in the southern half of the High Weald, where it was connected to the Kentish hop area… hop farming doubled in the High Weald between 1821 and 1874 and came to represent a quarter of national production. Hops were a high risk, but high profit crop, which required the in-migration of a lot of seasonal labour around harvest time.” So hops was a profitable, but high risk crop which boomed in Sussex at the time of Catherine Ann’s marriage to Philip Morris.

Writing in the late 1800s, Kent MP, Mr. H. T. Knatchbull-Hugessen, described women’s role in hops cultivation, “In the winter… women and children shave the poles for use in the spring… The position of the hop-grower is as difficult and dangerous a one as exists in any department of agriculture.” We do not, however, know if Catherine Ann was obliged to shave hops poles during winter months to keep Brett’s Farm in the “state of high cultivation” described in its 1860 auction notice. What we do know is that she had at least five children. Her three girls, Mary, Eliza and Barbara, are listed in the 1841 census staying with her unmarried sister, Mary Harmer, in a townhouse in Cliffe, Lewes, along with the children of their other sister, Mrs Elizabeth Walls. It may be that unmarried Mary Harmer served as a babysitter while Catherine Ann laboured on the farm co-managed by her husband and her brother “two hats” Harmer (who – as attested in a news clipping cited in HFA March 2021 – paid the Cliffe house’s rent). The suggestion is that Catherine Ann’s life as a farmer’s wife was too labour-intensive for her to cope with the additional demands of childcare. Or had Catherine Ann, perhaps, succumbed to health difficulties? She bore no further children after her 4th child, Barbara, in 1833 (my 2nd great-grandmother). As a comparison, Catherine Ann’s sister, Elizabeth, bore at least seven children with her husband, Benjamin Walls, and seems to have borne an additional eighth, ill-fated infant prior to their marriage. The only record for this illegitimate-seeming child is provided by an 1804 Newick burial inscription for an infant intriguingly named “Benjamin Walls Harmer”.

Later records show that Catherine Ann remained close to her children. After her middle daughter, Eliza, married Henry Osborne Weaver, a Brighton-born assistant silk merchant, in February 1853, Catherine Ann was staying in the newlywed’s Southwark home ten months after their marriage. Southwark at this point was known as a slum area, and sanitation was dire. Catherine Ann succumbed to cholera, a disease virulent in 1850s Southwark, on 17th October 1853. Her son-in-law, Henry Osborne Weaver, died of the same disease five days later. Her brother, “two hats” died visiting the same Southwark house in 1859, and her husband, Philip Morris, outliving them all, was buried in Newick in 1864.