Lily Style Author

Capo Noli Battle Exhibition

How Nelson’s First Naval Victory Is Aiding Modern European Unity

(First published in the Kedge Anchor in 2019)

I was fortunate, on 30th March 2019, to attend the launch of a major exhibition of archaeological finds from Nelson’s 1795 battle with the French at Capo Noli (just off the coast of the modern Italian Riviera). The exhibition also included finds from the Republican army’s overland campaign in the area around the town of Finale Ligure, which is hosting the exhibition. The exhibition is being temporarily housed in the town’s Museum of Archaeology, but will be transferred to a new, purpose built museum once it has been completed.

Myself and my seven-year-old daughter Sophie were invited to the exhibition launch as descendants of Nelson. Also invited were Charles Napoleon Bonaparte and Paolo Caracciolo, descendant of Admiral Francesco Caracciolo, whose Sicilian fleet fought alongside the British at Capo Noli. For those of you familiar with Nelson’s later dealings with Caracciolo, I confess that, on learning he would be a co-attendee, to initially having feared some kind of Wicker Man style revenge plot! However, the organisers, the 1795 Association (founded in December 2018), assured me through our English-speaking liaison (an American author and local resident, Tom Mueller) that their intention was to dedicate the exhibition to a Europe able to reflect on its its history, and find reasons for pride, union, and awareness that so many achievements of our modern civilisation were born in our shared past. Their view of Nelson is of a hero of the wars who, in the end, successfully put an end to the Napoleonic threat. Their wish, therefore, is that our shared history, regardless of ancestral sides, represents a unifying common heritage. It was in this spirit, and as Chair of Emma Hamilton Society, that I produced portraits of Nelson and Emma, printed onto tiles, and inscribed with good will wishes in English and Italian, to be presented to the town of Finale Ligure, Paolo Caracciolo and Charles Napoleon Bonaparte at the exhibition launch.

The exhibition’s entire story, in fact, can be viewed in terms of modern day people, both amateur and specialist, passionately collaborating to bring our shared history to life in a way that is unifying on many levels.

The story begins in the summer of 2018 when two amateur divers, Marco Colman and Mario Arena, discovered something unusual in the sea off the coast of Finale Ligure at a depth of sixty-four metres. They showed a photo of their find to local history enthusiast, Alessandro Garulla (another skilled amateur) who was able to discern from the size and shape of the mysterious object that it was a French one pounder canon from the period of the Battle of Capo Noli.

The great depth at which the canon rested, however, rendered it impossible for the amateur divers to examine it in detail. They could only remain at that level for minutes before the intense pressure forced them to re-ascend and decompress slowly to avoid the bends (also known as decompression sickness).

Undeterred, Alessandro Garulla and the newly formed 1795 Association called in Italian special forces divers, who had the physical training and technology to explore the area around the sunken canon for substantially longer periods of time. A member of this elite team, Andrea Puleo, told me they had worked on the sixty-four metre deep site for four hours in the morning, and four hours in the afternoon every day for six days, remaining in compression the whole time by way of a live-in compression chamber on board their ship. “That sounds very tiring?” I suggested. “Oh yes,” he beamed, “we are trained to be very strong.” The special forces divers had, I was told, very much enjoyed taking this turn at marine archaeology because, unlike in other missions, there were no human corpses to recover. Instead of dead bodies, they found an entire gun casemate from Ça

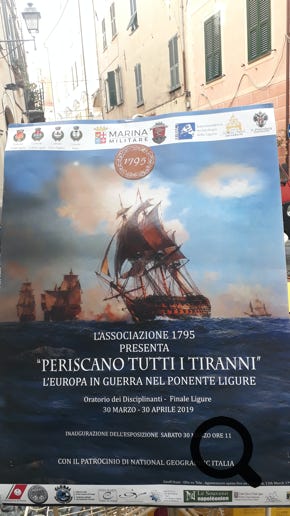

Ira, the very ship which, on 14th March 1795, Nelson, commanding the much smaller Agamemnon, attacked when spotting it fleeing and damaged. However, despite her damage, Ça Ira’s superior firepower could have easily obliterated Nelson’s ship. Yet his bold gambit paid off and Ça Ira was captured with Agamemnon having suffered no loss or damage. This was Nelson’s first naval victory, and it is incredible that a physical relic from it was retrieved from the deep seabed two-and-a-quarter centuries after the battle took place. Geoff Hunt’s painting of Agamemnon blasting Ça Ira was emblazoned on every exhibition poster pinned up in the town.

The land-gleaned artefacts displayed in the exhibition tell another story of the how passionate amateurs can play a major role in historical curation. I was told that every relic of the French Republican army on display had been unearthed during the course of the last fifty years by local enthusiasts with metal detectors. They had kept their finds, including pistols, swords and saddles, secreted in their private homes until the ‘mothers and fathers’ of Finale Ligure, as part of the enthused preparations for the new exhibition, called on the populace to bring their prizes forth. The wealth of these artefacts on display, which the townsfolk have donated for no financial gain, shows the level of civic pride the 1795 Association’s project has generated.

The launch was preceded by a pageant of Napoleonic era reenactors. David and Martin, British Napoleon enthusiasts who had traveled to the launch, told me they’d at first assumed the reenactors were simply having fun dressing up in period costumes, but had since learned that their costume and paraphernalia were so intricately researched that academics sought their knowledge: in other words, the reenactors were not simply ‘cosplayers’, but valued experimental archaeologists: another example of impassioned amateurs contributing to academic knowledge. The assembled line of Republican troops outside the museum comprised gendarmes (in mustard waistcoats and trousers); and volunteers, of whom those dressed in off white were wearing old royalist uniforms, despite fighting for the other side. Andrea, the special forces elite diver, is a reenactor himself, and was keen for us to see them parade. The reenactors, in fact, clearly love having the opportunity to wear their reconstructed Napoleonic era attire, and could still be seen in full regalia the following day strolling around the old town centre and seated at outside cafe tables chatting amicably together in the sun.

My daughter Sophie was asked to hold the ribbon whilst myself and Charles Napoleon Bonaparte shared a pair of scissors to make a symbolic, joint cut: the exhibition was thus opened by ancestral enemies united. I had the honour of meeting Paolo Caracciolo as well as Charles Napoleon Bonaparte at the launch. Paolo, an unassuming, genial man who works as a travel agent, graciously accepted the tile I presented to him inscribed in English and Italian with a message of good will and reconciliation. I felt very moved to then shake hands with him. Charles Bonaparte proved more loquacious; a charming, softly spoken philanthropist. He told me that, as a youth, he had rejected his family’s heavy conservatism – in modern France, only the royal line, and Bonaparte family have recognised lineage – and, to his father’s disgust, embraced socialism instead. In later life, however, he felt inspired to use his family name to figurehead a historical tourism enterprise. He founded the (European Federation of Napoleonic Cities) in 2004 with the ethos of preserving common cultural heritage linked to the Napoleonic era, and highlighting this era’s influence upon contemporary Europe. He believes that awareness of shared history is of utmost importance so that we can learn from it. Much of his Federation’s work is to arrange European funding for the preservation of Napoleonic era sites to encourage cultural tourism. He had just returned from a trip to China where, he said, there is much awareness of Europe’s Napoleonic wars, and, therefore, scope for the development of tourism from China to "Napoleon Cities”. These have so far been established in France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Belgium, Germany, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Poland, Lithuania, and, as European Union membership is not essential for the securing of EU development funding, Russia and Egypt. He began talks in south-west England with Plymouth City Council and the University of Plymouth in late 2018 with a view of gaining European funding for the development of local Napoleonic era – or should I say Nelson era?! – sites, such as Dartmoor Prison. His Foundation also wants to create tourism projects in Finale Ligure, with a mountain bike route being one possibility. The concept of a bike route connecting Napoleonic era sites immediately reminded me of the The 1805 Club’s Trafalgar Way project. That both 'ancestral sides’ are seeking to preserve relics, and increase popular interest through touristic development feels immensely positive to me. You can learn more of Charle’s work at www.napoleoncities.eu, which has an English language option.