Lily Style Author

Home | Ancestry scrapbook | Contact | Facebook

Byzantium forever

originally published in The Historical Times in 2023

I first visited Turkey in March 1994 with my friend Stu. A Kurdish carpet-seller, named Rasim, accosted us in Istanbul’s historic district of Sultanahmet and took us to an outside cafe. We drank hot çay in tulip-shaped glasses, grateful for the brief respite from the clamour. The plaza between us and the towering minarets of the Ayasofia and the Blue Mosque was filled with men and head-scarfed women touting Turkey’s flag of a white crescent moon and star on a red background. Rasim told us the crowd had gathered because it was a Friday – Islam’s holy day – during Ramazan (the fasting month that’s named Ramadan in Arabic).

Cafes and shops blared music from cassette tapes – though never during the call for prayer. A favourite was Istanbul not Constantinople by They Might be Giants. “This is a very good song,” Rasim opined. “You know our city used to be called Constantinople?”

I was vaguely aware that Constantinople had been the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire until the Turks conquered it. Istanbul’s countless mosque-domes and minarets were clear indicators to me that the modern city was irrevocably Islamic. My sense of Constantinople’s obliteration increased with every glimpse of Turkey’s flag, whose star and crescent motif symbolises Islam. The same symbol features on the flags of Muslim countries worldwide, including Pakistan, Malaysia, Singapore, Tunisia, Mauritania, Tunisia, Algeria and Turkmenistan.

Byzantium’s true story, however, is markedly different from the tragedy of cultural obliteration I’d assumed. According to Herodotus, Byzantium was founded in about 667 BC. Legend tells that the city took its name from its founder, King Byzas. Byzantium was made capital of the newly-created Eastern Roman Empire in 330 AD when the Christianised emperor, Constantine, established himself there; called it the second Rome; and renamed it Constantinople to celebrate his own glory. Although the term Byzantine derives from the city’s name, it wasn’t coined until a century after the Ottomans seized it in the 15th century. The Greek-speaking, pre-Ottoman population thought of themselves as Roman, not Byzantine.

When the Ottoman emperor, Mehmed II, took Constantinople in 1453, he restrained his army from butchering the Greeks; converted the Hagia Sophia – the largest Christian cathedral of the time – into a mosque; and titled himself Caesar of Rome. A large population of Roman/Byzantine Greeks remained in the city, and across wide swathes of Anatolia. Ottoman administration permitted Greeks to practise their religion, but granted them fewer rights than their Muslim neighbours.

At its peak in the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire stretched from Vienna to the Persian Gulf. However, the majority of the empire’s population was Christian, not Muslim. In other words, Byzantine Greeks were still there in force.

The Ottoman Empire had dwindled into a weak shadow of its former glory by the start of the twentieth century. Its ruler, Sultan Mehmed VI, allied with Germany in World War 1 and, after Germany’s defeat, ceded the empire to the victorious Allies to divide up as they pleased. Greece wanted Anatolia because, historically, it had been part of the Greek-speaking Byzantine empire. When a force of 20,000 Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna (modern-day Izmir) in May 1919, they were supported by the Allies and not hindered by the sultan. A Turkish army officer named Mustafa Kemal organised like-minded Turks to rebel against Mehmed VI’s capitulation and prevent the Greeks from taking Anatolia. He replaced the Sultanate with a Turkish republic in 1923, and took the name Atatürk (father of the Turks). If the Greek army hadn’t tried to wrest Anatolia from Turkish control, Atatürk might have acted differently, but, as it was, he instigated an exchange of populations between the newly-defined boundaries of Greece and the his hard-won republic of Turkey. Every Turk living in Greece was relocated to Turkey, and vice versa.

The interrelatedness of Byzantine and Turkish culture prior to the population exchange is eloquently put by historical fiction author, Louis de Bernières, in a passage describing the state of Anatolia after the Greeks left:

almost no one remained who knew how to get anything done. There had been such a clear division of labour between the former inhabitants that when the Christians left, the Muslims were reduced temporarily to helplessness. There was no pharmacist now, no doctor, no banker, no blacksmith, no shoemaker, no saddle-maker, no ironmonger, no paint-maker, no jeweller, no stonemason, no tiler, no merchant, no spicer. The race that had preoccupied itself solely with ruling, tilling and soldiering now found itself baulked and perplexed, without any obvious means of support.”

However, just as Neanderthals live on in the DNA of non-African people, Byzantine “DNA” is clear as daylight in 21st century Istanbul, if we know where to look.

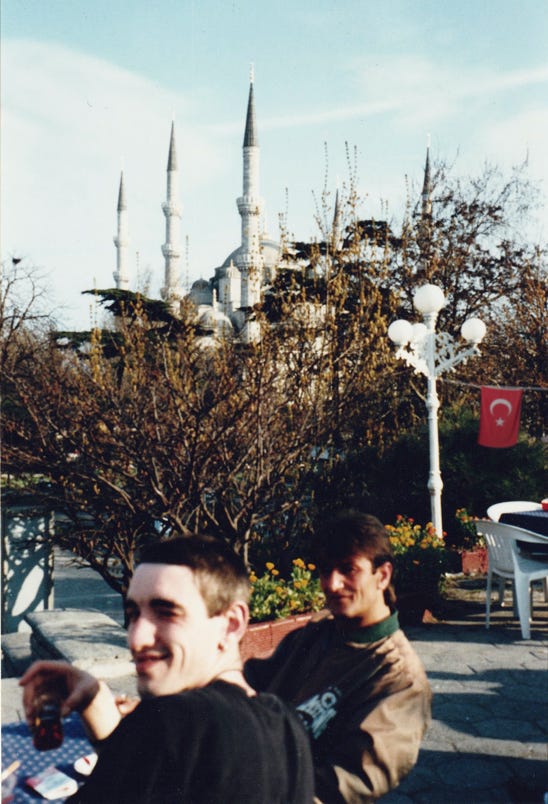

Another view from the cafe: Stu and Rasim with the Blue Mosque behind them, March 1994 (author’s photo).The Ayasofia, whose towering minarets were surrounded by Turkey flags when I first visited Istanbul, is the Byzantine Hagia Sophia, whose cathedral dome still dominates the city skyline two millennia after its construction. Though minarets were added to it by the Ottomans, a wealth of Byzantine artwork remains inside. Atatürk converted it into a museum in 1934.

The menus of the eateries nestling around the Ayasofia, such as the one I sat in with Stu and Rasim in 1994, are choc-a-bloc with Greek dishes, such as moussaka and “çoban salatası” (shepherd’s salad) containing feta cheese. In fact, Turkish and Greek cuisine merged so tightly during Ottoman rule that it’s hard to tell from whom they originated. For example, the name of the classic Greek dish “dolmades” (stuffed vine leaves) derives from the Turkish verb “dolmak” (to stuff), whereas the word “moussaka” (“musakka” in modern Turkish) seems to be of Greek origin.

Perhaps the most remarkable legacy of Byzantium is the star and crescent symbol of Islam that features on the flags of Muslim countries around the world.

According to legend, in 340 BC, Philip of Macedon – father of Alexander the Great – attempted to seize Byzantium in a surprise nighttime raid. The city was saved by a bright light that appeared in the sky to illuminate Philip’s army. Alerted, the citizens of Byzantium succeeded in repelling the Macedonian army. They believed the light had been a gift from the moon goddess, Hecate. They adopted the star and crescent as Byzantium’s symbol in honour of the goddess.

There’s irony that the people who finally did take Byzantium – the Ottoman Turks – co-opted Byzantium’s symbol of salvation from invasion; and that their symbol now represents Islam, whose name means peace from submission to God… but perhaps this isn’t ironic because the Byzantine people survived by peacefully submitting to their conquerors.